Reviving Civil Society is Key to Good Government

In 1996, Harvard University professor Robert Putnam gave the annual Manion Lecture in Ottawa, sponsored by the Canadian Centre for Management Development. The title of his address was The Decline of Civil Society: How Come? So What? It was four years before the release of Putnam’s book Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community, a seminal work that to this day remains a defining and insightful analysis on the decline of civil society in the United States.

By Dale Eisler, JSGS Senior Policy FellowIntroduction

The book charts the weakening of what he terms “social capital” in the U.S. since 1960 and its corrosive effects on society and government. Putnam’s lecture served as a preview of what was to become Bowling Alone.

In his address he talked about a 20-year sociological and political study he and colleagues did on “the character, quality and performance of local government in Italy.”1 Years earlier a set of regional governments had been established across Italy that Putnam said were “genetically identical” because they all looked the same on paper. However, the outcomes were far different. Some regional governments were quite effective and successful. Others, in his words, were “disasters”.

What Putnam found was that it was not the relative wealth or poverty levels of the different regions that explained the differences. The best predictors of government performance were, amazingly enough, things like “choral societies, football clubs, rotary clubs, reading groups and hiking clubs.”2 In other words, social capital as expressed by civil society was the key to good government. “Some of these communities had dense networks of civic engagement. People were connected with one another and with their government. It wasn’t simply that they were more apt to vote in regions with high-performance governments, but that they were connected horizontally with one another in a dense fabric of civic life,” Putnam said.3

So, what exactly is civil society that produces the social capital important to successful government? One definition by the Centre of Public Legal Education is concise and to the point: “Civil society is the activity of citizens and organizations in free association without the authority of the state, and without the motive of profit.”4

Social capital as described by Putnam comes in two parts – bonding and bridging social capital. Bonding social capital networks connect people to one another within the group. Bridging social capital connects members of one group with other groups across society. It serves as an essential ingredient to the fabric of a cohesive and well-functioning society which Putnam said was in a state of decline and had been for years. “By virtually every conceivable measure, social capital has eroded steadily and sometimes dramatically over the past two generations,” Putnam wrote in Bowling Alone.5

Although Putnam’s lecture was almost 30 years ago and his book on the same subject appeared four years later, many would argue that his thesis on social capital and good governance remains even more relevant today than when it first appeared. And for good reason.

Decline of public trust

One of the key issues Putnam explored in those days was the decline of public trust in government and other institutions in the U.S. In his lecture he said: “It is not only distrust of government that has grown, and certainly not just the federal government. It is also a distrust of state and local government, a distrust and lack of appreciation, lack of approval, of the performance of most of the institutions in our society. Trust in business is down, trust in churches is down, trust in medicine is down. Trust in - I am sorry to have to say this - trust in universities is down. We have this feeling that none of our institutions is working as well as it did twenty or thirty years ago.”6

If that observation sounds familiar, it should. The decline of trust in government and other institutions is also evident in Canada. One clear expression of that sentiment has been a corresponding decline in the number of people who show up to vote in elections. If there is one indication of people disengaging from the broader society, it is expressed in voter turnout. Lack of trust in government leads to apathy in the election process itself.

In the 2021 federal election, voter turnout was 62.6 per cent. As recently as the 1988 federal election voter turnout was 75.3 per cent. We have witnessed a steady decline over the last three decades, with the lowest point being a voter turnout of 58.8 in the 2008 election.7 The same holds true at the provincial level. For example, in the 2020 Saskatchewan provincial election only 52.9 per cent of eligible voters actually cast a ballot. In 1982 the number of eligible voters who voted was almost 30 per cent higher at 79.8 per cent.8

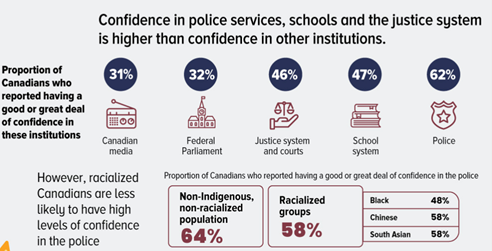

Another measurement reflecting the loss of public trust that goes beyond government is done annually in the Edelman Trust Barometer, a global assessment that measures trust in government, business, media and non-government organizations. In its 2024 report that surveyed 28 countries, Canada ranked 14th with a score of 52 on a scale of 100. In a report issued in April of this year, the Environics Institute stated: “Canadians are losing trust in the ability of both the federal government and their provincial governments to deal with key issues such as health care, climate change, immigration or the economy.”9 A recent literature review of research into public trust levels in Canada carried out by the University of Waterloo reflected those findings. “Many surveys have consistently found that Canadians’ overall trust in most institutions and public figures has been low recently and was low before the pandemic, with total rates of trust between one third and one half of the public being typical,” the Waterloo report states.10

This all raises the question of why have we seen this weakening of the social fabric? In Putman’s opinion, a key reason as far back as the 1990s was that, quite simply, people were doing less and less things together. As a result, the social capital so important for a well-functioning and engaged society had been steadily undermined. The sense of community and collective welfare was eroded.

Fast forward to today and that diagnosis quickly comes into focus. Its relevance is undeniable. The emergence of social media and a world interconnected by the Internet has fundamentally changed how people communicate and engage, or, more to the point do not engage with others. In political and governance terms, it is most pronounced in the way people self-select their interests and biases and retreat into online silos determined by those preferences. While some might argue those communities of interest are simply 21st century examples of civil society in a different form, they are also by their nature impersonal. The result is far less human-to-human connection than was the civil society reality of several decades past.

One small, but relevant piece of evidence in Canada has been the decline of service clubs and volunteerism. The Covid pandemic is often cited as a major cause, but the trend has been evident for decades. “We’re losing the groups that bring people together at the local level and that provide space, tools and money to support community causes. We’re losing churches, service clubs, auxiliaries and other groups that provide the structure for volunteering at the local, regional and national levels,” says Don McRae, a board member of Volunteer Canada.11

Service clubs such as the Lions, Kiwanis and Elks have been in decline for many years. Two years ago, Statistics Canada reported that in the non-profit sector 67 per cent experience a shortage of new volunteers, 51 per cent have challenges with retention, and 26 per cent report high volunteer burnout and stress.12

This disconnection between individuals and their communities is evident in many forms. One is the demise of traditional local media, in particular the dying newspaper industry. At one time, the local newspaper was an essential ingredient in defining and shaping community interests among its readers. Those days are gone. Now most people get their news and information on the Internet, often from social media sources that provide no sense of “place”.

Accepting the reality of a more disengaged and disinterested population in terms of community, resulting in the decline of civil society identified by Putman almost three decades ago, the challenge becomes what, if anything, can be done about it? Is there a policy solution by government to an issue that itself, by definition, is unrelated to government?

When discussion turns to causes in the decline of civil society it often unfolds in ideological terms. Some argue it’s a result of the growth of government in the economy and society that has crowded out the role previously played by civil society, thereby weakening social capital. Others maintain the expansion of government has given stability to services that before were at the mercy of volunteerism and the goodwill of individuals. In other words, government policy has given permanence to the support that builds social capital.

But what no one can deny is that much of the organically occurring connective tissue within communities that was evident years ago has diminished.

Are there Policy Solutions?

Those who have studied the decline of civil society agree that one consequence is less effective government. People become disinterested, apathetic and cynical. What can result is a populism fueled by anger and alienation from the institutions of society. We certainly are witnessing these impulses in much of today’s public dialogue in Canada, the U.S. and many places around the world.

A paper by Ottawa-based Institute on Governance argues that successful democracies like Canada’s have a long history of constructive engagement between civil society and government. But the reality is now different. “Today, huge new trends – including the emergence of social media, the rise of populism, the disruption of mainstream media, the ongoing digital revolution, and accelerating globalization – are transforming our society … Sharp declines in both social cohesion and trust in public institutions are deeply worrying consequences. These two factors are vital to a healthy democracy, and the pressure on governments to respond is growing.”13

Clearly, rebuilding a more engaged and robust civil society is a complex challenge that goes far beyond government policy. But government, and certainly politicians, can play a more constructive role by fostering a more inclusive environment that seeks accommodation and consensus rather than conflict. Language, tone and the expression of shared values matter. It starts by accepting the diversity of views and encouraging public engagement, including from the voices of dissent, as part of building a sense of belonging to the broader community, whether it’s the town, city, province or nation where you live.

Dale Eisler

Dale Eisler is Senior Policy Fellow at the Johnson Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy (JSGS). He is also a Director with the Canada Energy Regulator. A former senior federal public servant, he served as Assistant Deputy Minister at the Department of Finance, Assistant Secretary to Cabinet in the Privy Council Office, Consul General for Canada based in Denver, CO. and ADM of Energy Security at Natural Resources Canada. After leaving the federal public service, he became Senior Advisor on Government Relations to the president of the University of Regina and a member of the university’s executive team, a position he held until 2020. Before his career in government, Dale was a Saskatchewan-based newspaper journalist and senior writer for Maclean’s Magazine based in Calgary. He holds a Bachelor and Masters degree in Political Studies. He’s the author of four books. His most recent "From Left to Right: Saskatchewan's Political and Economic Transformation" was shortlisted as 2023 political book of the year by the Writers’ Trust of Canada and won the Saskatchewan Book Award for scholarly writing. His previous book on Saskatchewan called “False Expectations: Politics and the Pursuit of the Saskatchewan Myth”, was published in 2006. His 2010 historical novel Anton, a young boy, his friend and the Russian Revolution became the basis for the feature movie Anton shot on location in Ukraine.

References

[1] The Decline of Civil Society: How Come? So What?, Robert Putman, speech delivered to the Canadian Centre for Management Development, Ottawa, ON. Feb. 22, 1996

[2] ibid

[3], ibid

[5] p. 287, Putnam, Robert, Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community

[6] p.5, op-cit

[7] https://electionsanddemocracy.ca/elections-numbers-0/graph-voter-turnout-federal-elections

[8] https://cdn.elections.sk.ca/upload/2020-Statement-of-Votes-Volume-1-web-viewing.pdf

[10] p.4 Trust in Canada: Recent Trends in Measures of Trust, TRuST Scholarly Network, University of Waterloo, April 2024

[11] https://carleton.ca/panl/2023/volunteer-charities-close-at-alarming-rates/

[12] https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/221125/dq221125b-cansim-eng.htm

[13] p5. Rebuilding Cohesion and Trust: Why Government Needs Civil Society, Institute on Governance, 2019