The grim reality of Canada’s biggest policy failure

When it comes to judging a public policy approach, the starting point is to agree there is a reality that, based on existing social and economic norms, is unacceptable. With that as context, ask yourself this question: what has been, and continues to be, the biggest public policy failure in Canada? By any objective measure the answer has to be Indigenous and Aboriginal policy.

By Dale Eisler, Senior Policy Fellow, JSGSWhen it comes to judging a public policy approach, the starting point is to agree there is a reality that, based on existing social and economic norms, is unacceptable.

With that as context, ask yourself this question: what has been, and continues to be, the biggest public policy failure in Canada? By any objective measure the answer has to be Indigenous and Aboriginal policy. In terms of social, economic and quality of life outcomes, nothing comes close to the failure of generation, upon generation of government policy relating to Indigenous people. Pick your measurement. Nearly every one of them leads to the same uncomfortable conclusion.

The litany of misery is well-known. But for sake of building consensus as a starting point, it bears repeating. That’s not to suggest there aren’t examples of positive economic and social results. There are success stories. But nor should we let that distract us from the hard truth.

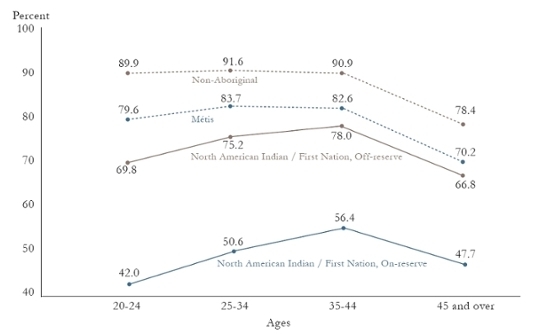

The issue is most grim in the context of child poverty. Fully 40 per cent of Indigenous children live in poverty—the total rises to 50 per cent on First Nations reserves—while the national rate of child poverty is 15 per cent.1 The official unemployment rate for First Nations people on reserves is 25 per cent, with 54 per cent dependent on government transfers as their primary source of income.2 Not surprisingly, educational outcomes are similarly bleak for Aboriginal people.3

Compared to the 90 per cent of non-Indigenous people aged 20-24 who received a high school diploma, the rate is only 42 per cent of Indigenous people.

One can go on. There are the desperate housing conditions for many on-reserve Indigenous people. Every so often reality confronts the public conscience when media report the Third World conditions some Indigenous people endure. One example from 2016 was the house unfit for human habitation on the Sandy Bay Reserve in Manitoba. Home to a family of 10, it had no proper sewage, clean water or insulation and was infested with rats. The chief of that reserve said 60 per cent of reserve residents live in sub-standard housing, in some cases with three or four families living in the same home.4 In response, Manitoba Chief Kevin Hart said at the Norway House First Nation they have 16-18 people living in two-bedroom homes. He went on to suggest the housing crisis will take a lifetime to resolve.

As you might expect, health outcomes are similarly grim. In 2005, The Globe and Mail’s health reporter Andre Picard reported infant mortality among Aboriginal children is three times the rate of non-Aboriginal kids. The suicide rate for Aboriginal people is six times higher than for others. On average, life expectancy for Aboriginal people is a decade less than for non-Aboriginal people. The story was headlined “Native health care is a sickening disgrace”. It opened with this assertion: “A mad scientist, hell-bent on destroying the health of a population, could probably not imagine a more diabolical plan than this one.5 The saddest part is that more than 12 years later, not a great deal has changed.”

Even the United Nations condemned Canada’s record in 2012, stating: “By every measure, be it respect for treaty and land rights, levels of poverty, average life spans, violence against women and girls, dramatically disproportionate levels of arrest and incarceration or access to government services such as housing, health care, education, water and child protection, Indigenous peoples across Canada continue to face a grave human rights crisis.” It was a declaration that outraged the federal government. But in terms of reality for many Indigenous people, it is difficult if not impossible to dispute.

So setting aside the residential schools fiasco, which is a whole other chapter of the same narrative, and without putting too fine a point on it, we should have our consensus: public policy outcomes for Indigenous people have been a disaster. Sure, people can point to progress in cases where there are stories of entrepreneurship and economic growth. But viewed over Canada’s history in any meaningful, long-term sense, the results have been mostly negative, and in many cases tragic.

However, cobbling together a consensus about failure is easy. The hard part is what to do about it. The issues are so interwoven in the history of colonialism, so deeply rooted in attitudes, patterns of racial discrimination, biases and cultural conflict, that the scope of the challenge seems beyond the reach of policymakers, whether Indigenous or non-Indigenous. The complexities of evolving legal decisions add to the challenge of reshaping the Indigenous and non-Indigenous relationship. But there is a glimmer of hope. Canada is in a moment when there is a national focus on the issues. Agree or disagree, the Trudeau government’s priority given to Indigenous issues provides a unique opportunity for real, meaningful and even radical change.

The defining core of the challenge is the intersection of European, or settler culture and norms, with the traditions and history of First Nations people. It is a relationship framed by the Indian Act, which sets in law the paternalistic and colonial relationship that many believe perpetuates the unacceptable and persistent outcomes from one generation to the next. Until Indigenous people can escape the constraints of the Indian Act and are given greater control over their lives—the idea of First Nations sovereignty and self-determination—nothing will fundamentally change. Indeed, the purpose of the Truth and Reconciliation process is an effort to come to grips with that history.

Having said that, for remote and isolated First Nations that lack either a significant population base of economic opportunity, reaching and maintaining an acceptable standard of living will be an enormous challenge. Clearly there is no single remedy. However, we’re at a point when creative thinking that questions the status quo is needed and even being welcomed, at least rhetorically, by the federal government.

Ideas worth considering

A significant part of the challenge is its scope. The issues can seem so daunting and complex that people feel overwhelmed. In that reality, focusing on real change on a manageable and relatively small scale can provide for incremental, but important progress.

Two ideas, which were briefly on the public agenda in recent years, deserve to re-enter the public dialogue. Both sought to increase control of Indigenous people over their lives and both relate to forms of governance. The first is about treaty modernization to empower individual status Indians. The other is about giving First Nations people the ability to control and fix what is, in many circumstances, a broken education system.

Treaty annuity

It was the late Jean Allard, a Métis and former member of the Manitoba NDP government of the early 1970s, who wrote and spoke passionately of how to restore the power, influence and dignity of individual treaty status people. Allard argued that the imposition of governance systems on First Nations has corrupted and distorted traditional First Nations practices. Prior to non-Indigenous governance systems being implemented, Allard says individual band members had influence through their loyalty to the band. If they were unhappy with their community, they were free to join another band. The strength of a chief was directly related to the loyalty of the number of band members, who had the power of mobility. Allard bases his arguments on Treaty Six and leaders such as Chief Big Bear who believed the treaty annuity—or “treaty money”—empowered individuals within the band collective. He saw it as crucial under the new constraints and changes to traditional Indigenous life imposed by treaty and the loss of mobility created by a reserve system.

The implementation of the Indian Act and the non-Indigenous concept of elected democracy to replace traditional Indigenous forms of consensus, Allard argued, is a core reason for the outcomes we witness today. In effect individual First Nations people have no power. “Chiefs, councils and their allies—who make up the ruling elite—exercise power and control over the lives of people who live on reserves that is unheard of in a democratic society. They control everything,” Allard wrote.6 It’s a consequence of funding to First Nations that is transferred from the federal government directly to Chiefs and councils as the duly elected representatives of the band members.

To restore some power and influence to individuals, Allard argued for the modernization of the treaty annuity paid to individual band members. Other aspects of treaties, such as the original idea of a “medicine chest”, have been modernized to mean delivery of health care. So too has the federal government’s responsibility for housing, education, economic development and welfare programs, which have evolved and expanded over time. As you would expect, federal programming for First Nations has also grown significantly, especially since the late 1960s, and totals approximately $10 billion a year. There is another $3.2 billion a year for First Nations and Inuit health care.7 Virtually all the money flows directly from the federal government to First Nations governments and their institutions.

What remains an artifact of the 19th century and hasn’t changed is the treaty annuity of a few dollars to each status Indian.

If the treaty annuity was “modernized” and adjusted to current dollars, Allard estimated in 2002 it would equal about $5,000 per person. He based his calculation on the value of an acre of land in 1871 at the signing of Treaty Six, compared to today’s market rate. So instead of the current $5 a person, a family of four would receive $20,000 in today’s dollars. Not enough to support a family, but clearly significant enough to make a difference in their lives. But most important is that the direct transfer to individuals would restore a measure of the individual sovereignty that has been lost with the First Nations governance based on non-Indigenous models applied to First Nations. “The primary intent of the treaties was to provide land for the band and an annual payment of treaty money to every man, woman and child in that band to be spent as they choose,” Allard argued.8 The issue of a modern treaty annuity is currently being tested in an Ontario court where 21 First Nations are arguing the annual Robinson-Huron treaty payment of $4 has not been adjusted for 150 years. The First Nations position is that the treaty annuity was supposed to rise as resource revenues generated by the territory covered by the treaty also increased.9 An enhanced treaty annuity, rather than the anachronistic and ceremonial “treaty money” of today, is not without significant issues.

For example, it would apply only to numbered treaties, leaving out the north, Arctic Quebec, Labrador and B.C. It also would amount to a guaranteed annual income, which no doubt some will argue would only further embed a culture of dependence imposed for generations by non-Indigenous society on First Nations people. Moreover, an enhanced annuity would inevitably mean a reduction in other funding that currently flows to First Nations governments.

One could also take the concept to its logical extreme. In that event, all funding would go to individual status Indians living on reserves, with First Nations governments then funding themselves through taxation of their members, as happens in broader Canadian society. The argument is that taxation of individuals to finance the interests of the collective is critical to assure government transparency and accountability to its electors. But that kind of radical restructuring of a system imposed and deeply embedded by the Indian Act would do far more harm than good. The key is a policy that restores the right balance in power between the individual and the collective. A modernized treaty annuity would be a small step in that direction.

But discussion or debate of a way forward also needs to be realistic. It must be driven and determined by Indigenous people themselves, both their elected governments and the grassroots. Trying to overcome the effects of a system more than 150 years in the making requires accepting certain facts, including geographic isolation that severely limits the potential for economic opportunity.

Education system reform

The second and arguably more crucial idea is reform of First Nations education. No issue is more important to improving the lives of current and future generations of First Nations people than ensuring a system of education that meets their needs. As the graph below indicates, the gap in educational outcomes between students attending First Nations schools and the general population is stark, particularly for the 20-24 age cohort which reflects recent performance of First Nations schools.

With the support of then Assembly of First Nations Chief Shawn Atleo, former Prime Minister Stephen Harper attempted to tackle the issue. The ill-fated Bill C-33 proposed to give First Nations control of their education systems and committed to annual increases of 4.3 per cent a year in funding for First Nations education. But the legislation died in the face of opposition by many First Nations Chiefs amid accusations of insufficient consultation and funding.

Figure 1: High School Certification or Above

For all its shortcomings, the proposed legislation was still an incremental step forward. It sought to address an education system that, based on objective outcomes, is failing First Nations children. The challenges of First Nations education have been on the public agenda for years. In 2011, a Senate report characterized the issue by saying: “The federal role is not merely to fund First Nations educational services; it is to work, hand in glove, with First Nations to help build their educational capacity and institutions so that they are able to deliver an effective educational program to their students, comparable to provincial and territorial offerings.” 10

Paul Martin, another former prime minister, has also focused his energies and philanthropy, since leaving politics, on Aboriginal education. The Martin Aboriginal Initiative is about improving outcomes for elementary and secondary Aboriginal students by supporting target programs in the classroom that meet the needs of the students. A primary criticism Martin makes is that per student funding for First Nations students fails to match that of non-Aboriginal students. Although some dispute the claim of underfunding, former TD Bank Senior Vice-President and Chief Economist Don Drummond calculated that First Nations children living on reserve get 30 per cent less in funding.11

Many argue that aside from proper funding, the key issue is one of governance and structure, specifically the creation of First Nations school boards. A 2016 C.D. Howe paper by Barry Anderson and John Richards on band-operated schools noted: “With few exceptions, reserve schools yield poor results on basic measures of standard academic performance.”12 Most First Nations schools operate independently or in very small groups, many with small numbers of students, and a teaching staff in constant flux. Since the 1930s in the rest of Canada, schools are part of school boards or divisions that create the critical capacity of resources and administrative expertise, as well as public oversight through school board elections, to ensure quality education. The need for First Nations school boards was the central argument of a 2009 Caledon Institute Paper by Michael Mendelson. “Whole system reform is exactly what is urgently required for First Nations education,” Mendelson wrote. He went on to note that “the old village school, sometimes operating under the administration of the town mayor, is long gone everywhere – except on First Nations Reserves … if First Nations are to have a school system, and not just a collection of schools, full control and ownership of schools must be vested in First Nations school boards and not individual bands.”13 The Prince Albert Tribal Council in Saskatchewan has taken significant strides in this direction by creating an education board, and similar progress has occurred in Nova Scotia, and also B.C., where on-reserve outcomes are significantly better than in other western provinces.

Conclusions

Ultimately, the way forward comes down to a choice between the scale of the approaches to be taken. The depth of the challenge is such that there will be those who argue what’s required is a massive public commitment, a kind of Marshall Plan for Indigenous people. It would address the issues head on, whether it is alleviating poverty, improving education outcomes or finding ways to create sustainable economic opportunity. Certainly each of those is part of the solution. But so too is a realization that outcomes demonstrate the current system and structures are failing Indigenous people.

Given the scope of the challenge, the ideas of a modernized treaty annuity and creation of First Nations school boards are hardly radical. Alone they will not resolve issues that are deeply embedded in a history of colonialism, clash of cultures and the racism evident in Canadian society. But they do represent attempts finally to begin changing policies created by a system that has failed generations of Indigenous Canadians. But whatever policy direction is taken it must come from Indigenous people. Anything less will merely continue the sad history of Canada’s greatest public policy failure.

Works Cited

1 Poverty or Progress, Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, June 2013

2 p. 13 Aboriginal Economic Progress Report, National Aboriginal Economic Development Board, 2015

3 Statistics Canada

4 http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/manitoba/sandy-bay-first-nationhousing-1.3836216

5 Native Health Care is a Sickening Disgrace, The Globe and Mail, November 2005

6 p. 130, Big Bear’s Treaty, The Road to Freedom, Inroads Journal, 11

7 Treasury Board Secretariat, 2017-18 Expenditures by Program and Purpose

8 Op-cit, p 163

9 http:www.cbc.ca/news/canada/sudbury/robinson-huron-treaty-annuitiesclaim-court-case-1.4303287

10 p.61 Reforming First Nations Education, Senate of Canada, Dec. 2011

11 http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/thunder-bay/first-nations-educationfunding-gap-1.3487822

12 p. 6 Students in Jeopardy: An Agenda for Improving Results in Banoperated Schools, Barry Anderson and John Richards, C.D. How Commentary No. 444, January 2016

13 pp.2,4,7, Michael Mendelson, Why We Need a First Nations Education Act, Caledon Institute, October 2009.

Dale Eisler

Prior to joining the JSGS, Dale spent 16 years with the Government of Canada in a series of senior positions, including as Assistant Deputy Minister Natural Resources Canada; Consul General for Canada in Denver, Colorado; Assistant Secretary to Cabinet at the Privy Council Office in Ottawa; and, Assistant Deputy Minister with the Department of Finance. In 2013, he received the Government of Canada’s Joan Atkinson Award for Public Service Excellence. Prior to joining the federal government, Dale spent 25 years as a journalist. He holds a degree in political science from the University of Saskatchewan, Regina Campus and an MA in political studies from Vermont College. He also studied as a Southam Fellow at the University of Toronto, and is the author of three books