Saskatchewan Potash Taxes and Royalties: Is it Time for a Review?

Potash production has long been important to the Saskatchewan economy. Consider: In 2017, exports of potash from Saskatchewan amounted to over $5.0 billion as compared to a Gross Domestic Product for the province as a whole of $79.5 billion that same year. According to the Mining Association of Canada, the province’s 10 producing potash mines have undergone significant investment activity, and the association identifies $9 billion in “recent” investments in the industry’s capacity.

By Jim Marshall, Executive-in-Residence, Johnson Shoyama Graduate School of Public PolicyPotash production has long been important to the Saskatchewan economy.

Consider: In 2017, exports of potash from Saskatchewan amounted to over $5.0 billion1 as compared to a Gross Domestic Product for the province as a whole of $79.5 billion that same year2. According to the Mining Association of Canada, the province’s 10 producing potash mines have undergone significant investment activity, and the association identifies $9 billion in “recent” investments in the industry’s capacity3.

Saskatchewan has been a leading producer of potash for world markets for at least 50 years and, in 2017, producing nearly 30 per cent of the world production of potash4.

Potash production has also been an important source of revenue for the Government of Saskatchewan, generating direct payments of $308.7 million in 2017-185. There are other taxes paid by the companies that operate the potash mines through either corporation income taxes, sales taxes, corporate capital taxes and resource surcharges and property taxes or from the individuals that work for those companies in income taxes, sales taxes and the like.

The global market dominance of Saskatchewan potash has inevitably given the resource unique stature in the province’s public policy dialogue. It has been reflected in recurring debates. First it was the acceptable levels of incentives to attract private investors in the 1960s, then it was potash nationalization in the 1970s, followed by privatization in the 1980s, and more recently the expansion incentives of the early 2000s and the merger of the Potash Corporation of Saskatchewan with Agrium to create the new entity of Nutrien.

Not surprisingly, in the production of any resource with the importance of potash, there will be ongoing discussion about the appropriate split of the proceeds from resource development between the owners of the resource, the people of Saskatchewan in this case, and the owners of the capital employed to extract the resource, the potash companies.

Although there have been calls for a revision to Saskatchewan’s potash royalty and tax structure from time to time, it has never been clear what the objectives of such a review should be. A review of any tax system should only be undertaken with some objective in mind.

As will be shown below, there is reason to believe that the share of potash revenue currently taken by the government of Saskatchewan is below levels previously collected by governments, suggesting that Saskatchewan’s current tax regime is far less lucrative for the people of Saskatchewan than has been the case in the past.

Industry Background

The potash industry in Saskatchewan has been dominated by two main players, Potash Corporation of Saskatchewan (PCS) and Mosaic, and one smaller producer, Agrium. In 2016, PCS reported production of 8.6 million tonnes of potash from its five Saskatchewan mines6. Mosaic reported that production from its three Saskatchewan mines totaled 7.1 million tonnes of muriate of potash in 20167. Agrium reported production of 2.2 million tonnes of potash at its one mine in Vanscoy in 20168.

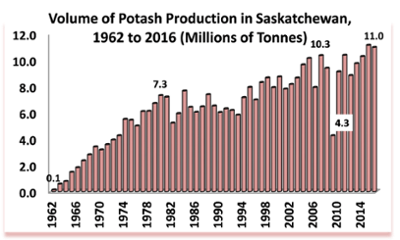

This total production of 17.9 million tonnes of KCl (potassium chloride) converts to an equivalent of about 11.1 million tonnes of K2O (potassium oxide) which is consistent with reported production of 11.0 million tonnes K20 reported in Figure 1 below, and suggests shares of Saskatchewan production in 2016 as:

- PCS: 48.0 per cent

- Mosaic: 39.7 per cent and,

- Agrium: 12.3 per cent.

Effective January 1, 2018, PCS and Agrium merged to form a new company, Nutrien, raising their combined share of production to 60.3 per cent of the total9.

In addition, K+S Potash Canada opened its potash mine at Bethune in May of 2017 and reported it hopes to achieve its full production capacity of 2.0 million tonnes by the end of 201710. Reports of actual production levels are not publicly available yet and it should be noted that rated capacity of mines is rarely achieved in actual production. Nevertheless, the new K+S mine could add as much as 11 per cent to Saskatchewan’s overall production of potash when it achieves full production levels.

While several other companies have expressed an interest in potash production in Saskatchewan, none is close to production at this time.

Potash Taxes

A simple overview of Saskatchewan’s tax treatment for potash was provided by D. Chen and J. Mintz in their assessment of the tax system in 201511.

“Saskatchewan’s Potash Fiscal Regime The Crown royalty: The effective royalty rate ranges from 2.1 to 4.5 per cent and the royalty base is the value of production priced for the lowest grade of product. The potash-production tax: Two layers:

(1) The base payment: the tax rate is 35 per cent and the tax base is a minimum of $11 and maximum of $12.33 per K2O (potassium oxide) tonne. The total base payment provides a credit for the Crown royalty and an additional one per cent resource credit that is based on the gross revenue. After these credits, any positive balance of base payment is creditable against the profit tax (see below) and negative balance is “restored” to zero. A 10-year holiday is provided for new investment projects.

(2) The profit tax: the tax rate is two-tiered, based on an annually adjusted profit bracket, which is $66.17 per tonne for 2014: 15 per cent on profit up to $66.17 and 35 per cent otherwise. The maximum taxable volume is the average sales in 2001–2002 for firms that existed then, and 75 per cent of total sales up to 1 million tonnes for newcomers. Under this profit tax, a 120 per cent allowance is provided for both exploration and development expenditures. Investment in depreciable capital exceeding 90 per cent of the 2002 investment level is also entitled to a 120 per cent allowance, and investment below 90 per cent of the 2002 investment level is written off at 35 per cent on a decliningbalance basis.

The resource surcharge: Three per cent on the sales value, akin to an ad valorem royalty but under the name of provincial capital tax.” 12

The authors were highly critical of this royalty and tax structure in Saskatchewan.

Of particular concern was the allowance of 120 per cent for exploration and development expenditures and for any investment in excess of the threshold of 90 per cent of the 2002 investment base.

It is usual for companies to be able to deduct these expenses up to 100 per cent, usually over a number of years. For example, the “normal” rate of deduction of capital investments at 35 per cent per year would allow a company to deduct capital cost over three years following a capital expenditure, even if that capital would last for many years beyond that.

By allowing a 120 per cent allowance, companies receive a significant incentive to invest through a faster allowance on the first 100 per cent of their investment and, in addition, are entitled to an incentive in being able to claim an additional 20 per cent against their income. At the lowest profit tax rate of 15 per cent this represents a de facto subsidy equal to three per cent of any capital or exploration and development expenditure and, at the highest rate, the subsidy grows to seven per cent of such expenditures.

Also of concern is the exemption from profit taxes on production levels in excess of the 2001-2002 levels for existing producers and the similar exemption provided on some of the production of new mines. These two exemptions, based on a point in time in the past, could provide a perpetual exemption if the industry grows to new production levels and could undermine the tax base in future years.

Examining the Trends: Splitting the Potash Pot

Historical production levels for potash in Saskatchewan are shown in Figure 1, below.

As Figure 1 illustrates, potash production in Saskatchewan has expanded significantly as the industry went through significant expansion during the start-up phase from 1962 to the early 1980s. Following that phase, there was significant variation in annual production rates until another expansion in output began in the early 2000s.

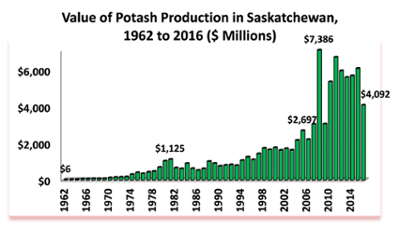

Figure 2 illustrates the value of potash production in Saskatchewan over the same time period.

Figure 2 illustrates that the value of production of potash followed the upward trend in volume of production during the early years from 1962 to the early 1980s and was more or less flat until the mid-1990s when it reached a new, higher plateau. The period from 2010 to the present has seen significantly higher values of production than has been experienced in the past.

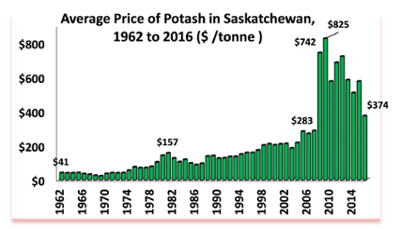

Average potash prices over this period are illustrated in Figure 3.

As can be seen from Figure 3, potash prices have seen a fairly constant upward trend until around 2008 when prices soared to a level of $742 per tonne. Although they have fallen back from that level in recent years, to around $374 per tonne in 2016, prices remain higher than their previous historical levels.

This sudden surge in potash prices, combined with the rise in potash production in the early 2000s as shown in Figure 1, explain the much higher values of potash production seen in the new century in Figure 2.

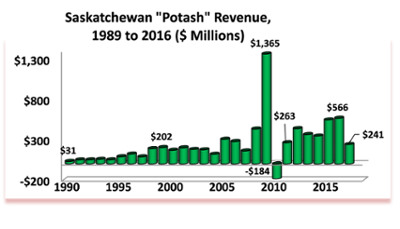

Saskatchewan government revenue from potash taxes and royalties, not including taxes of general application such as sales and income taxes, are shown in Figure 4 for the period from 1989 to 2016.

Figure 4 illustrates that there has been considerable year-to-year fluctuation in potash collections on the part of the province throughout the last three decades, a pattern exacerbated by an apparent anomaly in collections that occurred when overpayments made in the 2008-09 fiscal year had to be returned to the industry in the 2009-10 fiscal year.

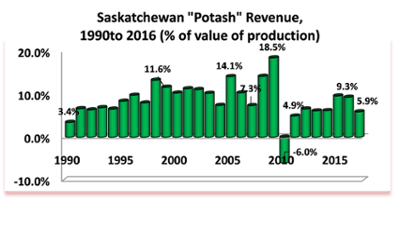

Figure 5 illustrates the province’s collections from potash production in terms of a percentage of the value of production shown in Figure 2.

As Figure 5 illustrates, effective average tax rates on potash production have fluctuated quite widely from year to year in Saskatchewan, from a low of 3.4 per cent of the value of production in 1990 to an anomalous high of 18.5 per cent in 2008-09.

In the 1990s, tax rates averaged around 8.1 per cent.

In the early 2000s, ignoring the anomalous years of 2008-9 and 2009-10, effective tax rates averaged around 9.5 per cent of the value of potash production in the province.

Since 2009-10, tax collections have averaged around 6.9 per cent of the value of production, down from the levels of the 1990s and the 2000s.

Conclusion

As was seen in Figure 5, effective tax rates on Saskatchewan potash have averaged around 6.9 per cent since 2009-10, down sharply from rates averaging 9.5 per cent in the early 2000s and 8.1 per cent in the 1990s. This variance of 1.0 to 2.5 percentage points in tax rates amounts to around $40 million to $100 million per year in potential revenue to the government of Saskatchewan.

If historical shares are to be taken as a guide, it would seem that any review of potash taxes in Saskatchewan could be expected to result in a greater share of the proceeds from potash flowing to the people of Saskatchewan through royalties and taxes than has been the case in recent years, as opposed to a shift in the split towards the producing companies.

The Mintz study identified a number of problem areas in the current potash tax system. It focused especially on the de facto exemption from the profit tax for any new production in excess of the 2001-02 base and on the generous 120% allowance provided for new capital expenditures.

Since the industry has had nearly 18 years of benefit from the exemption provided on new production, and as many years to benefit from these generous capital allowances, these two features of the potash tax system might be the first areas one should examine in looking for ways to restore Saskatchewan tax rates to more historic levels.

References

1 Government of Saskatchewan. Economic Review, 2017. P. 21.

2 Statistics Canada. Table 36-10-0222-01. Accessed November 13, 2018.

3 Mining Association of Canada. Facts and Figures of the Canadian Mining Industry, 2016, p. 25. Accessed November 13, 2018.

4 United States Geological Survey, National Minerals Information Center, US Mineral Commodity Survey, 2018. Accessed February 12, 2018.

5 Government of Saskatchewan, Public Accounts, 2017-18, Volume 2, p. 9. Accessed, November 13, 2018.

6 US Securities and Exchange Commission, Form 10-K Potash Corporation of Saskatchewan Inc., for the fiscal year ended December 31, 2016, p. 5. Accessed February 13, 2018.

7 US Securities and Exchange Commission, Form 10-K The Mosaic Company for the fiscal year ended December 31, 2016, p. 12. Accessed February 13, 2018.

8 Agrium, Annual Report, 2016, p. 31. Accessed February 13, 2018.

9 Giles, David. “PotashCorp, Agrium receive final approval for merger”, Global News. Accessed February 13, 2018.

10 K+S Potash at: http://www.ks-potashcanada.com/us/legacy/#bethune. Accessed February 13, 2018.

11 D. Chen and J. Mintz. “Potash Taxation: How Canada’s Regime is neither Efficient nor Competitive from an International Perspective”, SPP Research Papers, vol. 8, issue 1, Jan. 2015. Accessed February 13, 2018.

12 Ibid. p. 5.

ISSN 2369-0224 (PRINT) ISSN 2369-0232 (ONLINE)

Jim Marshall

Jim Marshall is currently a Lecturer and Executive-in-Residence at the Johnson Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy. Prior to this, Mr. Marshall served in the Public Service of Saskatchewan for 34 years, occupying senior policy and executive positions in the Department of Finance and Industry and Resources and at the Crown Investments Corporation. Prior to coming to Saskatchewan, Mr. Marshall lectured in economics at Brandon University and conducted research at the Library of Parliament in Ottawa. Mr. Marshall has lectured in economics and public policy at JSGS, the University of Regina, Faculty of Administration and the University of Regina, Department of Economics. He is a graduate of Brandon University and the University of Calgary.