Not all quiet on the equalization front in Canada

One of the most challenging and divisive public policy issues in Canada is the federal government's Equalization program. It seeks to ensure provinces have the fiscal capacity to deliver programs to their citizens on a roughly comparable basis. The formula to determine what provinces qualify to receive federal Equalization payments is by its nature a source of controversy. Recently Newfoundland and Labrador launched the latest court challenge to Equalization. In this Policy Paper for the Johnson Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy (JSGS), Louis Levesque, considered one of Canada's leading experts on Equalization, does a deep dive into the economic and regional considerations that lie at the heart of the issue.

By By Louis Lévesque, Former federal deputy minister, including lead at Finance Canada on EqualizationContext

Download the JSGS Policy Paper

Download the Discussion Questions

The resentment about the equalization program that has always been present to some extent in parts of the country is now being expressed formally. This past June Newfoundland and Labrador filed a constitutional challenge against key provisions of the current equalization formula in its provincial Supreme Court. The provincial government’s June 26 communique states:

“(this) statement of claim outlines how the Government of Canada’s equalization program does not achieve its constitutional purpose. The program unreasonably and unfairly penalizes Newfoundland and Labrador by failing to transfer sufficient funds which are needed to ensure that residents benefit from levels of public services that are reasonably comparable to those in other provinces.

Relief being sought from the court involves declaring elements of the equalization program as unconstitutional, including:

- The absence of including the costs of providing public services when calculating equalization payments;

- The fiscal capacity cap;

- The inequitable distribution of excess equalization program funding;, and

- The gross domestic product growth ceiling.”

Newfoundland and Labrador is not alone in expressing concerns about the Equalization Program. Saskatchewan's premier Scott Moe has been very vocal on this issue and his government tabled a reform proposal in 2018 that amounted to a 50% cut to equalization, combined with a redistribution of the savings on an equal-per-capita basis to all provinces. For its part, Alberta has expressed concerns over the years about the large sums coming out of the province to the federal government, notably to fund equalization payments. The Premier of British Columbia, David Eby, recently expressed similar concerns at the meeting of Premiers in July 2024.

Structure of the paper

This paper addresses all the elements in Newfoundland and Labrador’s legal challenge from an economist perspective. It also puts the political concerns expressed about equalization in their economic, demographic and fiscal context. This will show how opposite economic interests, largely around natural resource revenues, make it almost impossible for provinces to reach common ground regarding the equalization formula.

Based on those objectives, the paper starts with basic information about the equalization program. It then:

- addresses in detail and through a visual approach the issues related to the treatment of natural resources revenues under equalization and the fiscal capacity cap;

- discusses the absence of consideration of differences in expenditure needs between provinces;

- deals with issues raised by Newfoundland and Labrador relating to the growth envelope – floor and ceiling provisions; and,

- concludes with a discussion of the way forward.

Primary Findings

When the interests and objectives of the federal and provincial governments are explored, five core conclusions can be drawn.

First, relaxation of the fiscal capacity cap to allow for larger payments to Newfoundland and Labrador (and Quebec) could also potentially result in Saskatchewan qualifying for equalization payments. This would raise a major equity issue, first and foremost with Ontario.

Second, the size of Quebec’s population explains the province’s large share of total equalization payments. That share has been declining in recent years and may well continue to fall. However, Quebec has both the largest hydro resources and the lowest electricity prices in Canada. A case can be made that the current measurement of resource revenues in equalization encourages hydro producing provinces to maintain low electricity prices, thus discouraging energy efficiency, and needs to be revisited.

Third, integration in the equalization program of consideration of the differences in levels of per capita expenditure needs between provinces would be possible, but implementation would require time and resources for a significant analytical effort. It is far from clear however whether the result of such an exercise would indicate need for higher overall equalization payments or higher payments to provinces with smaller populations.

Fourth, the GDP growth envelope put in place in 2009 that led to floor payments since 2018 and the application of a ceiling to reduce payments before 2018 should be eliminated. This aligns in part with arguments made by Newfoundland and Labrador in its statement of claim and this is a change that the federal government could choose to enact at any time.

And fifth, the current equalization program largely reflects the 2006 recommendations of an independent panel that listened to all perspectives and examined in detail various options regarding the basic elements of the program. The recommendations from the O’Brien panel embodied a typical Canadian compromise balancing the diverging interests of the various regions of the country. Newfoundland and Labrador is asking a Court to overrule the decisions made by the government of the day that were subsequently made into law by Parliament, but a court is ill equipped to perform the required in-depth analysis of the underlying issues. A new comprehensive independent examination should be conducted before major changes to equalization are envisaged.

To begin: Basic information about the equalization program

|

Program History

|

(1) Making sense of the fiscal capacity cap

Determination of fiscal capacity is the key building block behind the calculation of equalization payments. Fiscal capacity refers to the ability of each province to raise own-source revenues. We first need to build an understanding of the differences in revenue raising ability between Canadian provinces to be able to discuss the fiscal capacity cap.

|

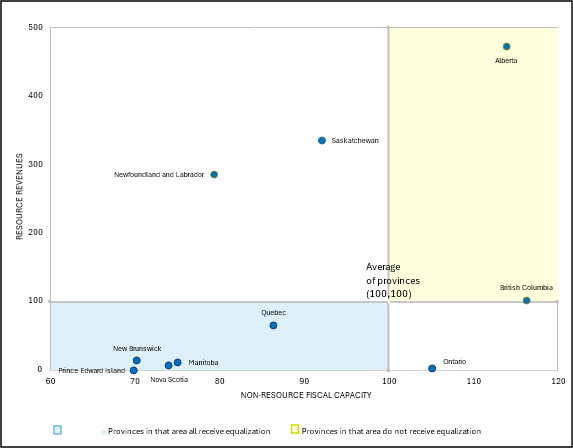

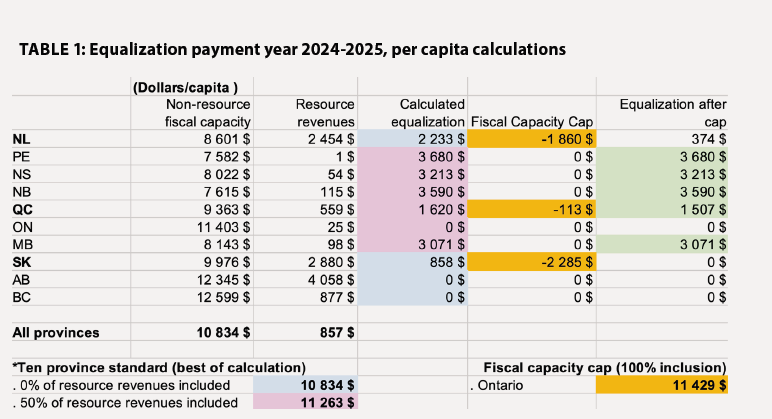

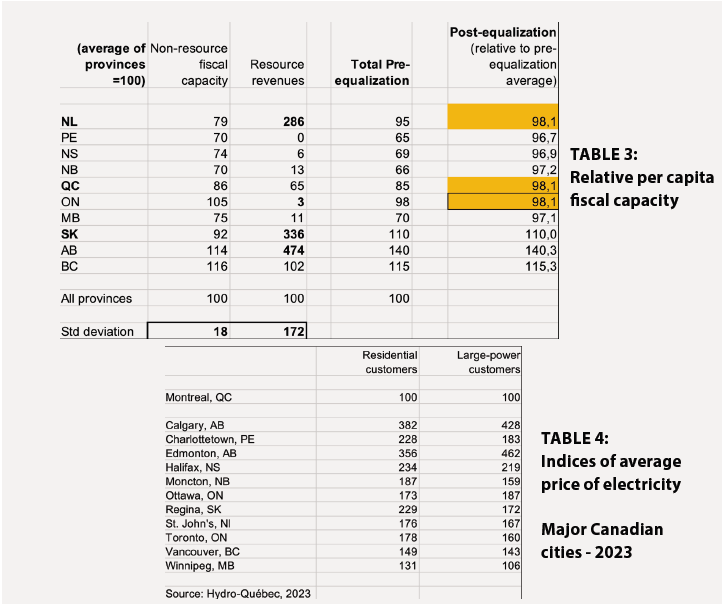

Understanding Chart 1 Chart 1 below presents visually the critical data related to the revenue raising capacity of provinces. Equalization treats revenues from natural resources, such as revenues from oil and gas or hydro, differently than revenues from sales taxes or income taxes. This is why they are represented on a different axis in the chart. The position of the blue dots represents the relative fiscal capacities of each province for non-resource revenues (horizontal axis) and resource revenues (vertical axis) in relation to the average of all provinces (100). We will use Saskatchewan to illustrate how the chart is constructed. Table 1 in the Annex shows that the province has a non-resource fiscal capacity of $ 9,976 per capita compared to the all-province average of $10,834, or about 92% of the average. For resources, Saskatchewan’s revenues amount to $ 2,880 per capita compared to the all-province average of $857, or about 336% of the average. Looking at the chart, the position of the blue dot for Saskatchewan, to the left of the vertical 100 line shows that the province has a slightly below average (92) non-resource fiscal capacity but its position much higher than the horizontal 100 line shows than the province has far above average (336) resource revenues. The same data for all provinces is shown in Table 3 in the Annex. The position of a province’s numbers relative to 100 is primordial for equalization as adoption of an all-province average (10-province standard) was a key part of the changes made to the program in 2007. It is also very important to note the differences in the scales of each axis. Non resource relative fiscal capacity (horizontal axis) ranges from 70 in Prince Edward Island to 116 in British Columbia. The disparities between provinces in per capita resource revenues (vertical axis) are ten times bigger ranging from 0 in Prince Edward Island to 474 in Alberta. |

The geography of Canadian equalization

Observing the position of the blue and yellow shaded areas in relation to the position of the average of provinces at (100,100) allows to already draw some conclusions. The five provinces in the blue shaded area will receive equalization payments as their non resource per capita fiscal capacity and their per capita resource revenues are both below the average of all provinces. Conversely, Alberta and British Columbia in the yellow shaded area should not expect to receive any equalization payments as they exceed the average in both types of revenues.

Chart 1: Relative per capita fiscal capacity of provinces -2024-2025 equalization payments

A definitive conclusion is not possible at this stage for Ontario, Saskatchewan, and Newfoundland and Labrador. Saskatchewan and Newfoundland and Labrador have lower than average non resource fiscal capacity but far above average resource revenues. Ontario has a slightly higher than average non resource fiscal capacity but very little resource revenues. Whether any one of these provinces qualify for payments and how much they end up receiving depend crucially on how natural resource revenues are treated in equalization.

The inclusion rate of natural resource revenues used to be the most important equalization issue

In Canada, the Constitution provides for provincial ownership of resource revenues. Federal legislation also provides for the delegation of federal authority over the offshore oil and natural gas in the Atlantic close to the provinces of Newfoundland and Labrador and Nova Scotia to these provinces. Natural resources are a significant source of revenues for provincial governments and are, as shown above, very unevenly distributed across the country.

Not surprisingly the provinces with minimal resource revenues typically argue for their full (100%) inclusion in equalization calculations. Conversely, provinces with large natural resource endowments argue that their citizens should be the principal beneficiaries of the development of these resources and that accordingly they should be excluded from equalization calculations.

With respect to non-renewable natural resources, a further argument is often made to the effect that proceeds from the exploitation of these resource should not be treated as current income but rather as monetization of a non-renewable asset. This argument has merit. It would be wise and prudent for provinces to emulate Norway and set aside and invest the lion’s share of their non-renewable natural resource revenues in a fund, and then only use the proceeds from the fund as revenues. This was the vision behind the decisions of former premiers Lougheed in Alberta and later Blakeney in Saskatchewan to establish Heritage Funds.

However, to this day resource-rich provinces essentially use most or all of the proceeds from resources as current income, allowing them to choose to have lower tax burdens or higher spending than other provinces. As a result, it is not possible to credibly argue that natural resource revenues do not contribute to fiscal disparities between provinces. Even more so, as we have seen above, these revenues are far more unevenly distributed than non-resource fiscal capacity. These facts make it impossible to reasonably justify a complete exclusion of natural resources revenues from equalization calculations.

The considerations regarding treatment of natural resources were front and centre in the deliberations of the O'Brien panel. The panel chose to recommend the compromise approach of including 50% of natural resource revenues in equalization calculations. The federal government instead decided in 2007 to adopt a best of approach, where each province would get at the beginning of calculations the higher amount of equalization calculated with a 50% inclusion rate or of that calculated with a 0% inclusion rate.

Calculating equalization payments

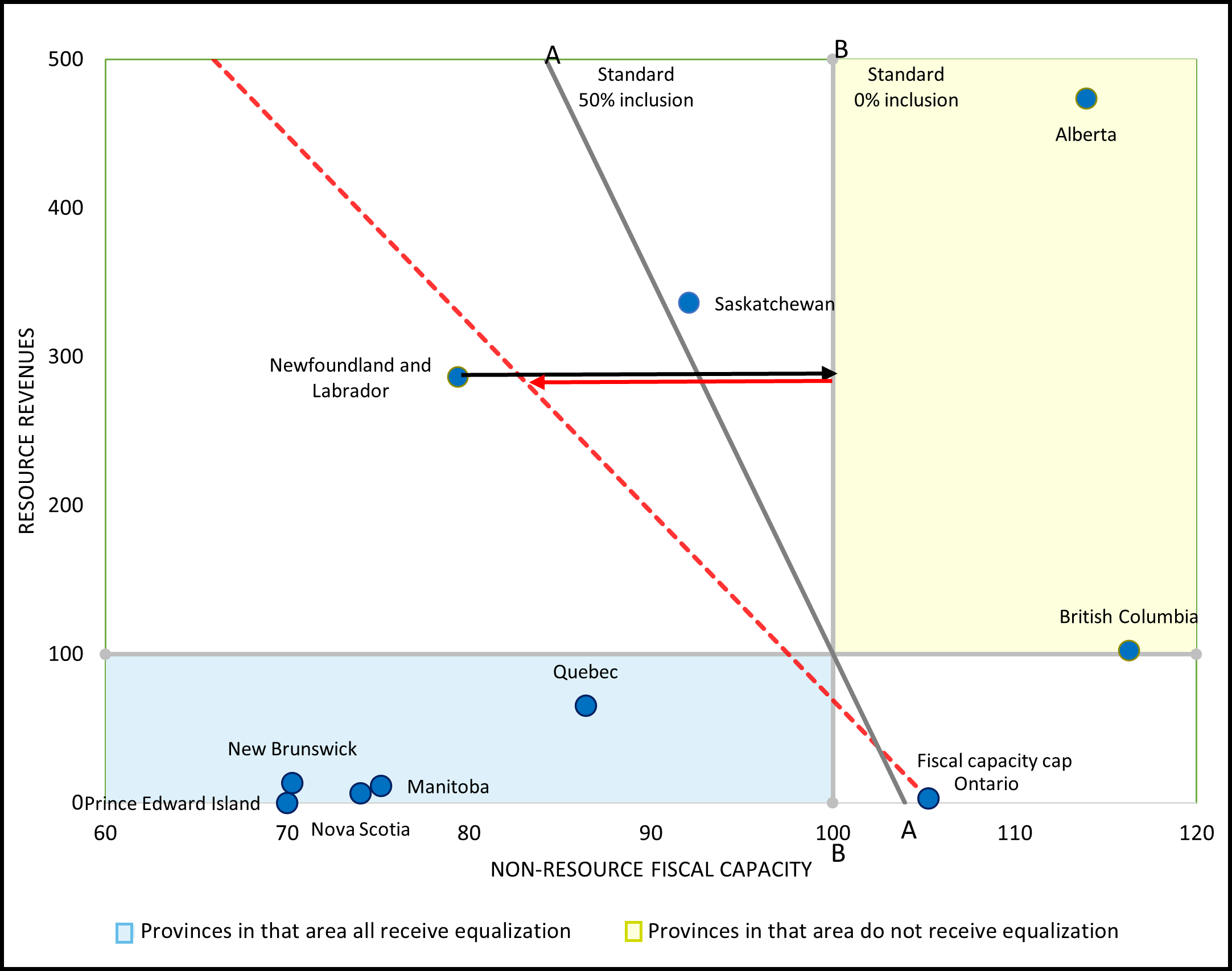

First step: best of 50% inclusion or 0% inclusion of natural resources.

A significant portion of discussions about equalization has traditionally revolved around the proper inclusion rates for natural resource revenues. Since 2007, calculating equalization for each province is determined to be the higher of the amount calculated using a 0% inclusion rate or the amount calculated using a 50% inclusion rate. Table 1 in the Annex shows the results for each province in the column calculated entitlements.

Second step: application of the fiscal capacity cap

While debates will continue about the proper inclusion rate of natural resource revenues in the equalization formula, another provision under the program - the fiscal capacity -cap is now a key element of the legal challenge by Newfoundland and Labrador.

Table 3 shows that Ontario has a non-resource revenue fiscal capacity slightly higher (105) than the national average, but little or no natural resources revenues (3). At the first step of equalization calculations, Ontario is the non-receiving province with the lowest overall fiscal capacity and becomes the anchor for the operation of the fiscal capacity cap.

|

Chart 2: Visualizing the calculations for Newfoundland and Labrador In chart 2, a new line has been added, the AA line, to represent the 50% inclusion rate natural resource revenue standard while the BB line (vertical axis) represents the 0% inclusion rate standard. Calculated entitlements for a province under either one of the standards will be positive if the dot of the province is situated to the left of the line representing that standard. Newfoundland and Labrador's calculated equalization is represented by the black horizontal arrow going from its dot to the BB vertical line representing the 0% inclusion rate. (For provinces with below average resource revenues, say New-Brunswick or Quebec, the AA 50% inclusion rate line would lie farther to the right of their dot and thus be more advantageous). The dotted red line added to the chart depicts all the combinations of natural resources revenues and non-resource fiscal capacity that would give a province a fiscal capacity equal to that of Ontario when resources revenues are included at 100%. Application of the fiscal capacity cap means that payments that would take Newfoundland and Labrador to the right of the dotted red line are clawed back to ensure sure that its fiscal capacity overall does not surpass that of Ontario because of equalization payments. This is represented in the chart by the red arrow line going horizontally from right to left from the 0% inclusion rate standard line (vertical axis) to the dotted red line, leaving the much smaller payments shown in Table 1. |

No need for arrows to get to the result in the case of Saskatchewan. Its dot lies to the right of the red dotted line, meaning its overall fiscal capacity is higher than that of Ontario before equalization payments. The fiscal capacity cap entirely rules out payments to the province. Table 1 in the annex confirms that the fiscal cap completely nullifies Saskatchewan’s calculated equalization and shows that payments to Quebec are also reduced.

The origin of the fiscal capacity cap can be traced back to the controversy that arose after Prime Minister Paul Martin signed new offshore agreements with Newfoundland and Labrador and Nova Scotia in 2005. (See box). The O'Brien panel saw little policy basis for federal payments resulting in an equalization receiving province having a higher fiscal capacity than that of any non-receiving province. It recommended that the fiscal capacity of the non-receiving province with the lowest fiscal capacity become an upper bound for the fiscal capacity after equalization of equalization receiving provinces.

Newfoundland and Labrador contends in its statement of claim that the operation of the fiscal capacity cap amounts to taking into consideration 100% of the province’s natural resource revenues, without giving it the benefit of a full 10 province standard program with 100% inclusion of natural resource revenues. That claim is hard to dispute.

What Newfoundland and Labrador fails to mention is that the level of equalization payments it receives already ensures it has as an overall fiscal capacity equal to that of Ontario, as shown in Table 3. It is the operation of the fiscal capacity cap that prevents equalization payments from raising its fiscal capacity to go higher than that of Ontario. This outcome is consistent with the basic principle of redistribution, to the effect that government can take from richer Paul to give to poorer Peter but should stop before making Peter richer than Paul.

The statement of claim filed by Newfoundland and Labrador argues that the current operation of the fiscal capacity cap is tantamount to expropriation of the province’s natural resources. In this respect, the federal government has strictly complied with terms of the legislation that delegated authority over offshore resources to Newfoundland and Labrador and Nova Scotia. Also, the treatment now afforded under equalization to revenues of Newfoundland and Labrador and Nova Scotia from the offshore, is the same as the treatment afforded under the program to the revenues of other provinces from deposits or exploitation of resources on land that are of provincial ownership under the Constitution.

Through its legal challenge, Newfoundland and Labrador is effectively asking a court to rule that the federal government has a constitutional obligation to make equalization payments in such a way as to possibly endow an equalization receiving province with a higher fiscal capacity than that of a non-receiving province. There is not any basis in policy for such an outcome, so it will be interesting to see what the courts will have to say about the issue.

For completeness, one must note that the operation of the cap applicable in 2024-2025 is in accordance with the recommendations of the 2006 O’Brien report. At the time, it was expected that Ontario would be the least wealthy non equalization receiving province for the foreseeable future. Contrary to expectations, Ontario qualified for payments under the new formula as early as 2008. The federal government immediately legislated an alternative application of the fiscal capacity cap to apply in such a situation.

With this change, when Ontario qualifies, the amount serving as a ceiling becomes the average of the fiscal capacity of the equalization receiving provinces recipients, and no longer the fiscal capacity of the lowest fiscal capacity non-recipient province. The legislation does not specifically identify Ontario, but its formulation - when the population of the provinces having calculated entitlements reaches 50% or more of the population of all provinces – describes a situation which in practice only occurs when Ontario qualifies.

As Ontario would only qualify for small per capita payments, this change was clearly intended to prevent provinces with significant resource revenues (Newfoundland and Labrador, Quebec and potentially Saskatchewan in such a circumstance) from leaping significantly above Ontario’s fiscal capacity because of equalization payments.

Controversy over offshore equalization offset payments

The controversy with Newfoundland and Labrador and Nova-Scotia over the offshore has never been about authority over resources or royalties, but about the interaction between the offshore agreements and the equalization program. When the original agreements were signed in the 1980s, it was well understood that the new revenues to be collected by these provinces would lead to a corollary reduction in their equalization payments.

The two provinces argued that they should derive a net fiscal benefit from the exploitation of these resources. They were successful in obtaining that the agreements concluded in 1985(Newfoundland and Labrador) and 1986 (Nova-Scotia) contain provisions establishing temporary compensatory payments, called equalization offset payments, reimbursing them part of the equalization losses resulting from these new revenues for 10 years after the start of oil or gas production, and this on a declining basis (100% in year 1, 90% in year 2, 80% in year 3, etc.).

Oil and gas production began in the 1990s and by the early 2000s both provinces were concerned that offset payments were in the process of disappearing. In 2005, at their request, the federal government concluded new agreements restoring for 8 years, with the possibility of extension for another 8 years, compensation payments for Newfoundland and Labrador and Nova Scotia equal to 100% of the equalization loss resulting from offshore revenues.

Among the other provinces, it was Ontario that reacted the most negatively to this decision, particularly because the additional federal payments would provide Newfoundland and Labrador with greater fiscal capacity than Ontario. The special treatment thus offered to offshore revenues also raised an important equity issue with Saskatchewan, a province that would qualify for equalization or get much larger payments, were it not for its large on land resource revenues.

The federal government of Prime Minister Harper elected in 2006 promised Newfoundland and Labrador and Nova-Scotia that equalization reform would not affect their benefits under the agreements signed in 2005. When the new equalization system was announced in 2007, it however included the fiscal capacity cap recommended in the O’Brien report.

To honor the commitment made to Newfoundland and Labrador and Nova Scotia, the federal government therefore offered the two provinces the possibility to remain in the pre-2008 equalization system if they wanted to retain all the benefits under their offshore agreement and thus not be subject to the individual fiscal capacity cap. This approach was implemented despite complaints from the two provinces to the effect that it was not truly respecting the promise made by the federal government.

Newfoundland and Labrador, the only province that had chosen the option of remaining in the pre-2008 regime, joined the regime applicable to all provinces in 2012 when its eligibility for benefits under its 2005 agreement ended. Its equalization payments have been therefore subject to the fiscal capacity cap since then.

The fiscal capacity cap is also likely to constrain Quebec’s equalization payments for years to come

As noted above, equalization payments to Quebec in 2024-2025 are being constrained by the fiscal capacity cap, a situation that may well continue in the coming years. The good performance of the Quebec economy in recent years may also result in much lower growth or even declines in overall payments to Quebec.

The text boxes below address two other issues that usually come up in discussions: the large equalization payments going to Quebec and the treatment of Quebec’s huge hydro resources.

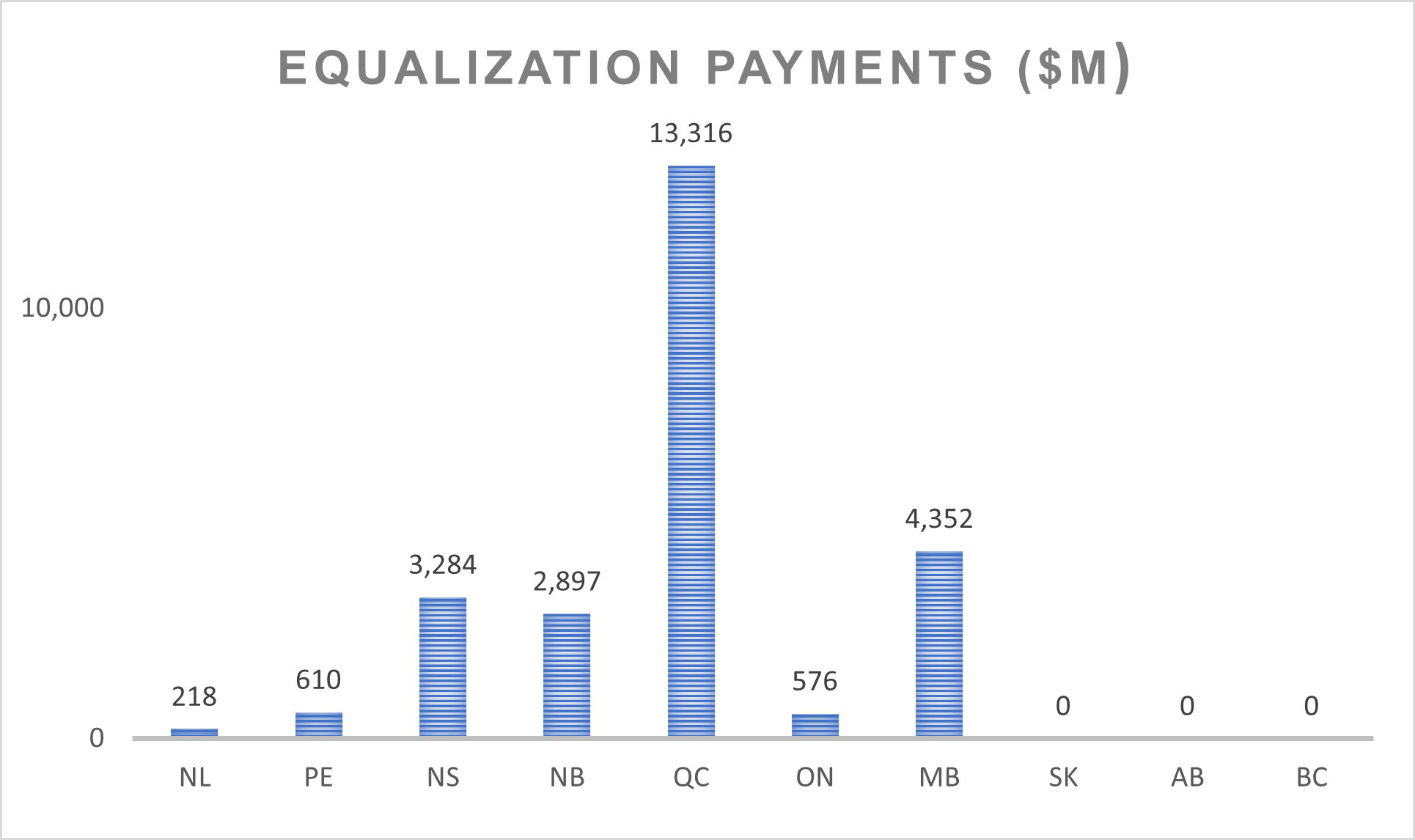

Quebec’s share of overall equalization payments has started to decline

The Quebec government is sensitive to the resentment elsewhere in the country associated with the fact that the province has been consistently receiving over the years more than half of total equalization payments, 53 % in 2024-2025 down from 66% in 2019-2020.

This is why the province always points out in its budget documents that Quebec is in fact receiving the lowest per capita payments among the five provinces – Quebec, New-Brunswick, Nova-Scotia, Prince Edward Island - that consistently receive equalization payments. This can be seen in the last column of Table 1. Quebec also correctly points out that the large share of overall payments it receives is rather the consequence of its much larger population compared to these provinces.

The current provincial government in Quebec City has made catching up to Ontario’s GDP per capita one of its stated medium term policy objectives and has welcomed the opportunity to become less reliant on equalization payments. In recent years, per capita GDP growth in Quebec has in fact been higher than in Ontario, thus narrowing the economic gap. If this trend were to continue, equalization payments to Quebec would have only one way to go, that is down, because increases in Quebec’s relative fiscal capacity will trigger decreases in the province’s equalization payments.

The measurement of fiscal capacity for hydro resources is increasingly problematic

Equalization calculations for non-resource fiscal capacity consider the revenues a province could raise if it applied tax rates equivalent to the average of all provinces. This is called the representative tax system (RTS) approach. This means that individual decisions by provinces about their tax structure, such as the decision of Alberta not to impose a general sales tax, do not result in inequitable treatment.

The RTS approach is not applied to resource revenues under equalization. The O'Brien panel noted that each resource project has a unique cost structure and that application of the RTS approach to resource revenues in equalization faced very difficult methodological challenges. The panel recommended instead that actual revenues raised by provinces from resources be used as the measure of fiscal capacity, a recommendation that was adopted by the federal government in 2007.

As a result, the current equalization system considers the revenues that the provinces choose to collect from the various natural resource revenue sources, assuming implicitly that provinces choose to collect all the possible revenues given market prices and the requirement for reasonable returns to investors.

The practice of oil-producing provinces of letting world markets determine the selling prices of their resources is consistent with that assumption. However, hydro producing provinces do not sell the majority of their electricity at market prices.

Quebec has by far the largest hydro resources among provinces. It is well known that Quebec offers its citizens and the large electricity consuming companies doing business in the province the lowest electricity rates in Canada. Table 4 helps illustrate the extent of the differences. Electricity rates in several cities located in the rest of Canada such as Calgary, Edmonton, Charlottetown, Halifax or Regina for residential customers are often more than double those of Quebec. In British-Columbia or Manitoba that also have significant hydroelectric resources, electricity prices are quite a bit higher than in Quebec.

An argument can be made that equalization indirectly encourages the maintenance of very low electricity rates in provinces with hydroelectric resources, particularly Quebec. This raises an equity issue with other provinces.

While Hydro-Québec’s key challenge for decades had been to find markets for its surplus energy, electricity surpluses in Quebec are now vanishing rapidly. Discussions about the need to raise electricity prices have been receiving more attention in Quebec recently.

Higher pricing would encourage energy efficiency but also increase Hydro-Québec's revenues which are taken into account in equalization. In the current program, an increase in H-Q’s profits of $100M results in a decrease in equalization payments received by Quebec of about $70M, a 70% recovery. In this light, one could also see the current equalization system as an energy inefficiency trap for Quebec.

While Quebec sees itself as a green province given that most of its electricity is produced by hydro, low electricity prices discourage energy efficiency in the province, but raising prices would entail large equalization payment reductions for Quebec. Quebec would be hard pressed to argue for special treatment should it decide to raise electricity prices in the province. The situation of Quebec is similar to that of Newfoundland and Labrador, the province having also already reached Ontario's fiscal capacity, after taking into account equalization payments.

The fiscal capacity measure for all natural resource revenues including hydroelectricity would be ideally based on the economic rent that could be drawn from these resources, taking properly into account the costs associated with the development of the resource. It is not clear whether a robust methodological framework can ever be built along such lines.

The current treatment of resource revenues under equalization reflects fundamental trade-offs, which were at the heart of the balance in the O’Brien Committee’s recommendations. A change in the treatment of hydroelectricity revenues under equalization therefore appears difficult outside a major reform to the program.

(2) Whether to take into account differences in expenditure need between provinces

The first element in the legal challenge by Newfoundland and Labrador against equalization is the program's failure to consider the various levels of expenditure required across provinces in determining equalization entitlements. The statement of claim correctly states that the cost to the province of providing its resident with the public services that are reasonably comparable to those available to residents of other provinces is not factored in equalization calculations.

This would not be grounds for a challenge if the overall per capita cost of providing comparable services was at the end comparable between provinces. This is why the statement of claim also argues that the cost of providing public services to the residents of Newfoundland and Labrador is higher than in other provinces due to factors such as the relative remoteness of the province, its geography and climate and the demographics, small size and socioeconomic circumstances of its population. In this regard, the vastness of Newfoundland and Labrador’s territory in relation to its population size, as well as the fact that its population is aging more rapidly than in the rest of the country cannot be denied.

There are indeed important differences between provinces in the per capita cost of providing certain services due to their geography or population characteristics. We should reasonably expect for example that the remoteness of Newfoundland and Labrador translates in higher need for road expenditures on a per capita basis.

Table 5 provides a simple estimate of relative per capita road maintenance costs across provinces using Transport Canada data about the number of kilometers of roads in each province. The data certainly appear to confirm that Newfoundland and Labrador’s per capita financial needs for road maintenance are higher (148) than the provincial average (100). The table also shows that relative need for road maintenance is in fact much higher in the Prairies, with Saskatchewan at the top (454).

But that would be just the beginning of an analysis about expenditure need. Officials from BC would argue that their road maintenance costs are underestimated by not considering the much higher costs of building roads in the mountains. Quebec officials would argue that their costs are also underestimated because the data fail to account for the fact that Montreal and Laval are located on islands, requiring a much larger number of bridge structures than in other provinces. Ontario could also argue that costs for transit systems should also be factored in as they are much higher in large cities.

The analysis would obviously need to also include the largest component of provincial expenditures, wages for public sector employees in the health and education sectors. An older population will require more employees for elderly care and more hip replacements, but probably relatively fewer teachers. Even more importantly, the cost of living in Saint John’s Newfoundland or Trois-Rivières, Québec is much lower than in Toronto or Vancouver. Ontario officials would likely argue (as they have done in the past) that equalization in fact overcompensates poorer provinces by not taking into account the differences in cost of living, and the consequential impact on wages and the unit costs of delivering services.

The above demonstrates that a thorough examination of both unit costs and volumes of most provincial and local services would have to be conducted to arrive at reliable and fair estimates of differences in overall expenditure needs across provinces. The experience of Australia demonstrates that it is possible to operate an equalization system that estimates both the differences in the capacity to raise revenues and the differences in the cost of providing services between provinces, taking into account all elements, including the age structure of the population, the degree of remoteness and the unit costs of delivering services.

However, it is far from clear that the result of such an exercise in Canada would support an increase in overall equalization payments or increased payments to provinces with smaller populations like Newfoundland and Labrador. This is because the reduction in equalization payments that could result from taking into account differences in unit costs could potentially be quite large and more than offset the increase in payments associated with taking into account higher volume requirements in certain services, such as road maintenance costs or care for the elderly.

The question is thus not whether Canada could conceivably modify its equalization system to take into account differences in expenditure need, but rather should it consider doing so? The O'Brien panel discussed this question and answered in the negative in its 2006 report. It took the view that such an approach would not be appropriate for Canada, which is a more decentralized federation than Australia. The panel rather suggested to the federal government to put in place sector specific transfers if it wanted to address visible disparities in access to certain services between provinces.

Since then, the federal government has taken some steps to recognize the circumstances of smaller population provinces by introducing a floor component to the distribution of funding for its infrastructure programs. The experience of Australia suggests that developing a robust methodology and producing the necessary data to include expenditure need in equalization could require a significant analytical undertaking spanning over several years. It will thus be very interesting to see how the courts choose to address this issue in the context of the Newfoundland and Labrador challenge.

(3) A simpler issue – the GDP growth envelope – floor payments and ceiling

The Newfoundland and Labrador challenge also takes aim at the provisions mandating a GDP growth envelope for equalization. The statement of claim correctly indicates that in 2009 the Budget Implementation Act added an additional rule to the equalization formula whereby equalization spending will grow at a fixed rate per year based on the three-year moving average of nominal gross domestic product (GDP) growth. This effectively put in place a fiscal override to the determination of equalization payments legislated in the 2007 Budget.

The 2009 budget explained that the change was driven by Canada’s desire to limit the potential growth of its expenses under the equalization program which had grown at a rapid pace in previous years, but also to ensure that provinces would be protected against sudden reductions in overall equalization payments. With the inclusion of Alberta's resources in the equalization standard in 2007, Finance Canada was very preoccupied that the high oil prices observed in 2008 and 2009 would endure and translate into large increases in equalization payments.

That concern was proven to be somewhat overblown. Oil prices retreated and eventually collapsed in 2014. In real terms, oil prices now stand 30% below their level of 2008. Also, given the massive increase in oil production in the United States, there is little risk that oil prices in real terms will go back to the levels seen in 2008.

Equalization receiving provinces criticized the imposition of a ceiling in 2009, but the cumulative net impact on payments has been quite modest, a federal saving of about $9 billion by the end of fiscal year 2024-2025, or about 3% of the $300 Billion in payments since 2009.

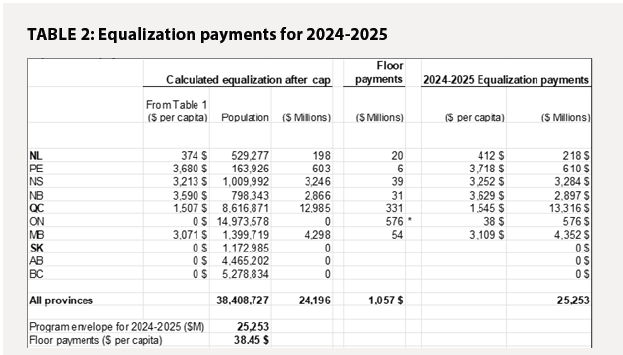

In fact, the tables have turned on the federal government. Since 2018, total payments calculated under the formula have been falling short of the program envelope and equal per capita floor payments are now being added to close the gap. In 2024-2025, the floor provision adds over a billion dollars to calculated payments as shown in Table 2.

If the rationale for the GDP ceiling was always rather weak, there is simply no basis in policy for a floor provision. The rationale enunciated in the 2009 budget to protect against sudden reductions in payments has little merit since that the program operates on a three-year moving average which already smooths out fluctuations.

Also, given the adoption of the 10-province standard in 2007, equalization payments before floor payments already bring all equalization receiving provinces to over 96% of the pre-equalization national average as shown in Table 3. Not surprisingly and with justification, the floor payments are now being criticized as excess generosity by non-equalization receiving provinces.

There is thus a clear case for the elimination of both the floor and ceiling provisions. Newfoundland and Labrador would rather see floor payments being distributed to all provinces, as opposed to only equalization receiving provinces as is currently the case, rather than being eliminated. It also attacks the GDP ceiling on the grounds it prevents the program from meeting its constitutional objective. It will be interesting to see what the courts say about that since the Constitution does not prescribe a precise level or formula for equalization payments. It is worth noting in this respect that, even with the ceiling, the equalization program currently in place is still more generous than the five-province standard regime that was in place for 25 years after the inclusion in the Constitution of a federal obligation to make equalization payments.

(4) The Way forward

The Trudeau government has not made any significant changes since 2015 to the equalization program that it inherited after the major reforms made under the Harper government. Regular reviews and discussions between federal and provincial officials were conducted and concluded in 2018 and 2023, leading to relatively minor changes. Equalization legislation was last renewed for 5 years as part of the 2023 Budget implementation legislation.

With a federal election very likely in the coming year a newly elected government will have to decide whether to make changes to equalization, or to leave well enough alone. Implementation of an overall expenditure restraint package might provide enough context for a new government to go ahead and get rid of the floor provision outside of the normal equalization renewal process. However, the possibility that Ontario could end up with the largest losses could tilt the balance against such a decision.

As explained above, major changes would require careful examination, consultation and federal provincial discussions to ensure all perspectives have been aired and listened to.

When the O'Brien panel was launched in 2005, the federal government already had a pretty good sense of what its recommendations would look like. The 10- province standard, the 50% inclusion rate for natural resource revenues and the fiscal capacity cap did not come as a surprise but rather as an expected typically Canadian compromise.

The situation is quite different today. As explained above, some of the fundamental questions that are being raised may not have a viable policy answer significantly different from the status quo. Some avenues, such as a thorough examination of expenditure need might also lead to conclusions radically different from the expectations of their proponents. But some, like the measurement of hydro revenues, will eventually need to be addressed.

The federal government will have to weigh those considerations carefully before launching a comprehensive review. Such an exercise would have to be to be properly scoped to minimize the risk of nurturing irreconcilable expectations. The credibility of the process would also need to withstand intense scrutiny.

The legal challenge by Newfoundland and Labrador might eventually end up before the Supreme Court of Canada. Newfoundland and Labrador is asking a Court to overrule decisions made by the government that were subsequently made into law by Parliament, but a court is ill equipped to perform the required in-depth analysis of the underlying issues. This legal process could thus end up prompting the federal government to undertake a major examination of equalization.

History has shown that while decisions by Canada’s highest court provide legal clarity, they often do not resolve the underlying political issues. In addition, as lawyers say it's often better not to ask a question of which you do not already know the answer.

Annex

|

The tables 1 to 3 below are based on Finance Canada official data for 2024-2025 payments. Finance Canada uses a large amount of information about provincial and local revenue sources, as well as population data from Statistics Canada. Revenues not related to natural resources include various types of personal income taxes, corporate taxes, sales taxes and property taxes. Non-resource fiscal capacity is determined using a representative tax system approach (RTS), whereas the capacity of each province for each tax base is calculated using an average national tax rate. Resource revenues include mining duties, forestry revenues, revenues from hydroelectricity as well as revenues from activities related to oil and gas production and exploration, both onshore and offshore. The RTS approach is not used to establish fiscal capacity for natural resource revenues under equalization. Actual revenues raised by each province are used in the calculations. A 3-year lagged moving average approach is applied to determine the data used to calculate equalization payments. The data used for the 2024-2025 calculations, reflect 2020-2021 data with a weight of 25%, 2021-2022 data with a weight of 25% and 2022-2023 data with a weight of 50%. |

The colour shading under calculated equalization in Table 1 corresponds to the inclusion rate used to determine calculated equalization for each province. The 0% inclusion calculation is more beneficial to provinces with higher-than-average natural resources revenues (in blue), such as Newfoundland and Labrador for which the calculated equalization ($2233) is the difference between the standard (10834$) and its non-resource fiscal capacity (8601$). The 50% inclusion rate calculation is more beneficial for the six provinces that have lower than average resource revenues (in pink).

The data in the third column of Table 2 show that equalization payments calculated from per capita amounts determined in Table 1 (24 196$M) do not fully expend the program envelope (25 253 $M). Equal per capita floor payments are added to this effect.

*Ontario’s calculated equalization after the cap is zero but the province still receives the same per capita floor payments. This is because the application of the fiscal capacity cap to Newfoundland and Labrador and Quebec means that these two equalizations receiving provinces have already reached the fiscal capacity of Ontario before the floor payments. Ontario has to be included in the floor payments to maintain this equality, as can be seen in the last column of Table 3 below.

Table 3 first shows the relative fiscal capacities of each province for the two types of tax bases. This is obtained by dividing the fiscal capacities for each province in the first two columns of table 1 by the average of all provinces (multiplied by 100). These data are used to plot provinces in the chart in the body of the text.

The table also shows the relative overall fiscal capacities of each province before and after equalization payments. A critical observation is that Newfoundland and Labrador and Quebec already reach with equalization payments the same overall fiscal capacity than Ontario. Any relaxation of the constraint imposed by the fiscal capacity cap in its current form would result in these two provinces having a post-equalization fiscal capacity higher than that of Ontario.

Louis Lévesque

Lévesque began his economist career in 1983 with the Quebec Government, first with the Crop Insurance Board and later with the Department of Finance. He joined Finance Canada in 1991 and moved up the ranks in economic development, tax policy and federal-provincial relations, leading to his appointment as Associate Deputy Minister of Finance in 2004. He was promoted to Deputy Minister in 2006 with responsibility for intergovernmental affairs in the Privy Council Office. He was appointed as Deputy Minister of International Trade in 2008, as Canada’s G-20 Sherpa and personal representative of the Prime Minister in 2010, and as Deputy Minister of Transport and Infrastructure Canada in 2012. Lévesque left the public service in July 2015 and later joined the International Forum of the Americas as Chief of Operations for the Montreal Conference. In April 2017, he was appointed as Chief Executive Officer of Finance Montreal, the cluster of financial institutions in Quebec. He currently devotes himself to consulting and lecturing. Born and raised in Quebec City, Lévesque obtained a first degree in Mathematics and a Masters in Economics from Laval University.