A case for renewal of municipal revenues in Saskatchewan

Municipal governments in Saskatchewan face significant challenges. An over reliance on property taxes, coupled with the need to address expanding social issues, service to citizens and infrastructure challenges has put enormous fiscal pressure on municipalities. It’s time to consider solutions that will make municipal governance more sustainable.

By Jean-Marc Nadeau, CEO, Saskatchewan Urban Municipalities Association (SUMA)Introduction

Download the JSGS Policy Brief

Download the Discussions Questions

It’s a long story, but an important one. To grasp the fiscal challenges faced by municipal governments, one must start at the beginning.

Canadian municipalities began forming in the 19th century. On the prairies, the first evidence of local government structures appeared around 1840 when organized settlements started providing treated potable water, wastewater management, and roads for property access (Archer 1980). However, it was not until a series of significant events—the formation of the Dominion of Canada through the enactment of the British North America Act of 1867, the passage of the Dominion Lands Act in 1872, the creation of the North-West Mounted Police in 1873, and the establishment of the pan-Canadian railway via a contract with the Canadian Pacific Railway in 1880—that growth in the municipal government sector was observed across the prairies. Following the establishment of Saskatchewan as a province in 1905, municipal governments were divided into three main legislated subsectors: rural, urban, and northern municipalities. Today, there are 296 rural municipalities serving nearly 16% of the Saskatchewan population, focusing primarily on maintaining roads and supporting the province's critical agriculture industry. The urban subsector encompasses 16 cities, 147 towns, and 281 villages and resort-villages, housing nearly 83% of the provincial population. Urban municipalities serve as vital hubs for economic and social activities for community residents and surrounding areas, including neighbouring rural municipalities. These hubs typically include retail and commercial businesses, financial and educational institutions, health services such as hospitals, clinics, long-term care facilities, recreational amenities like public pools, libraries, rinks, and ball and soccer fields. Urban municipalities also maintain fire and police departments that offer services to the broader region, not just the urban community. Northern municipalities consist of 35 communities, with a population of approximately 16,000 citizens or 1.5% of the provincial population, spread across the Northern Saskatchewan Administration District.

Municipal Government Challenges

Municipalities in Canada face numerous complex and unique challenges. This reality highlights the need for a new municipal revenue framework that provides municipalities with diverse, adequate, and predictable revenue sources to support their growing responsibilities and ensure a high quality of life for Canadians. To appreciate the public policy context, it is necessary to consider the range of significant issues faced by municipalities in Saskatchewan.

Since the province's inception in 1905, Saskatchewan municipalities have relied too heavily on an outdated revenue system. The system is based on a 19th century framework that depends on property taxes. It needs to be revised to meet modern service and infrastructure needs. The facts are that municipal governments are responsible for growing services, including housing, public transit, climate change adaptation, and public safety. However, their revenue sources have not kept pace with these expanding responsibilities. As a result, the current fiscal framework limits municipalities in many ways.

| 1986 | % OF CHANGE | 1991 | % OF CHANGE | 1996 | % OF CHANGE | 2001 | % OF CHANGE | 2006 | % OF CHANGE | 2011 | % OF CHANGE | 2016 | % OF CHANGE | 2021 | % OF CHANGE | |

| Total Saskatchewan | 1,009,613 | 988,928 | 990,237 | 978,933 | 968,157 | 1,033,381 | 1,098,352 | 1,132,505 | ||||||||

| Total Cities | 518,423 | 51.35 | 528,124 | 53.40 | 538,061 | 54.34 | 537,081 | 54.86 | 542,985 | 56.08 | 588,823 | 56.98 | 655,313 | 59.66 | 689,475 | 60.88 |

| Total Towns | 158,786 | 15.73 | 150,163 | 15.18 | 147,917 | 14.94 | 145,281 | 14.84 | 139,845 | 14.44 | 151,205 | 14.63 | 47,717 | 13.45 | 148,994 | 13.16 |

| Total Villages | 58,998 | 5.84 | 54,458 | 5.51 | 51,398 | 5.19 | 48,171 | 4.92 | 42,885 | 4.43 | 44,089 | 4.27 | 42,587 | 3.88 | 40,953 | 3.62 |

| Total Resort Villages | 1285 | 0.13 | 2,331 | 0.24 | 2,657 | 0.27 | 3,221 | 0.33 | 4,492 | 0.46 | 4,092 | 0.40 | 4,721 | 0.43 | 6,785 | 0.60 |

| Total Rural Municipalities | 231,119 | 22.89 | 209,923 | 21.23 | 197,131 | 19.91 | 187,825 | 19.19 | 175,659 | 18.14 | 174,585 | 16.89 | 176,525 | 16.07 | 176,501 | 15.59 |

Source: Saskatchewan Bureau of Statistics. Demography, Census Reports and Statistics

Population growth in Saskatchewan continues to present challenges for municipalities, particularly larger urban communities. Since the 1986 census (Table 1), cities have grown by 32%. Conversely, the populations of rural municipalities and villages have declined by 24% and 31%, respectively, intensifying the pressure on larger urban municipalities to deliver adequate services and infrastructure to accommodate this growth.

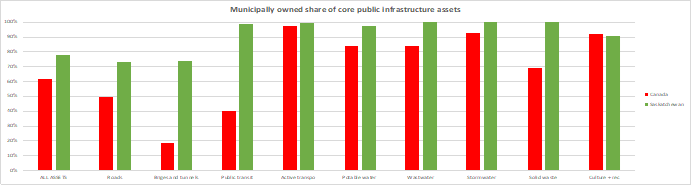

Another challenge for municipalities is that they own and maintain over 60% of public infrastructure in Canada (Figure 1) yet receive only 8-10 cents of every tax dollar collected. This creates a significant funding gap for maintaining and upgrading essential infrastructure.

Then, there is the complicated set of social issues that municipalities face. The urgent and growing problem of homelessness and housing affordability requires more predictable and adequate funding to invest in non-market and supportive housing solutions. At the same time, municipalities must deal with the impacts of climate change, which demands resources to invest in mitigation and adaptation measures to protect communities and infrastructure. Moreover, rising costs and the increasing complexity of public safety challenges, including policing and emergency services, demand more sustainable funding solutions.

Source: Government of Canada, “Estimated replacement value of core public infrastructure assets, by physical condition rating (x 1,000,000)”, Statistics Canada

The key to addressing the fiscal challenge is recognizing the overreliance of municipal governments on property taxes. A fundamental flaw is the inequity of property taxes, which can disproportionately burden lower-income families who may own less valuable property but still pay a similar rate as wealthier households with more valuable homes. In other words, low-income property owners spend a more significant portion of their net income on property taxes. This creates a considerable challenge for municipal councils, who must consider the impact of increasing property taxes on all property owners when establishing the municipal mill rate. Additionally, property tax revenue can be impacted by fluctuations in the real estate market, causing further issues during economic downturns when property values may decline, resulting in reduced tax revenue when municipalities may require more funds to support increased demand for services.

Governed by provincial legislation, municipalities have limited options for generating revenue, primarily restricted to property taxes, user fees, fines, and permits. They require greater autonomy to explore alternative revenue sources, such as local income or sales taxes, which could provide more sustainable funding and align better with the local economy. As previously noted, municipalities are increasingly tasked with a broad range of services; however, their revenue sources have not expanded in tandem with these growing responsibilities, resulting in financial strain. Municipalities depend on transfers from federal and provincial/territorial governments, which often focus solely on capital projects and typically do not cover operational and maintenance costs. Furthermore, these transfers can be unpredictable and come with strict application processes and reporting requirements, creating challenges for smaller municipalities.

Under the leadership of then Prime Minister Paul Martin, the federal government introduced the New Deal for Cities and Communities as part of the 2004 federal budget. Mr. Martin intended to modernize the relationships among federal, provincial, and municipal governments in Canada and improve infrastructure investment mechanisms. This initiative, shaped by asymmetrical federalism and historical federal roles in urban issues, was driven by six key factors: demographic shifts, globalization, quality of life, infrastructure deficits, municipal fiscal capacity, and environmental sustainability. It included a framework with a vision that included a federal urban lens, financial resources, and collaborative relationships supported by principles like respect for jurisdiction and transparency. The initiative resulted in a $5 billion investment from federal gas tax revenue over five years, enabling municipalities to address sustainable infrastructure needs. Overall, the New Deal was a comprehensive national effort involving all Canadian provinces, territories, and municipalities, with lasting positive impacts. In the context of funding and support, the federal New Deal for Cities essentially ended after the Conservative government, led by Prime Minister Stephen Harper, came to power in 2006. The new government shifted its priorities, and while certain funding commitments were continued, the specific initiatives and funding mechanisms associated with Martin's New Deal for Cities were not fully sustained or were revised under the new administration. The Harper government made some adjustments, introduced the Gas Tax Fund (GTF), and made the funding permanent instead of subjecting it to the annual budgets. The GTF was renamed the Canada Community-Building Fund (CCBF) in 2021.

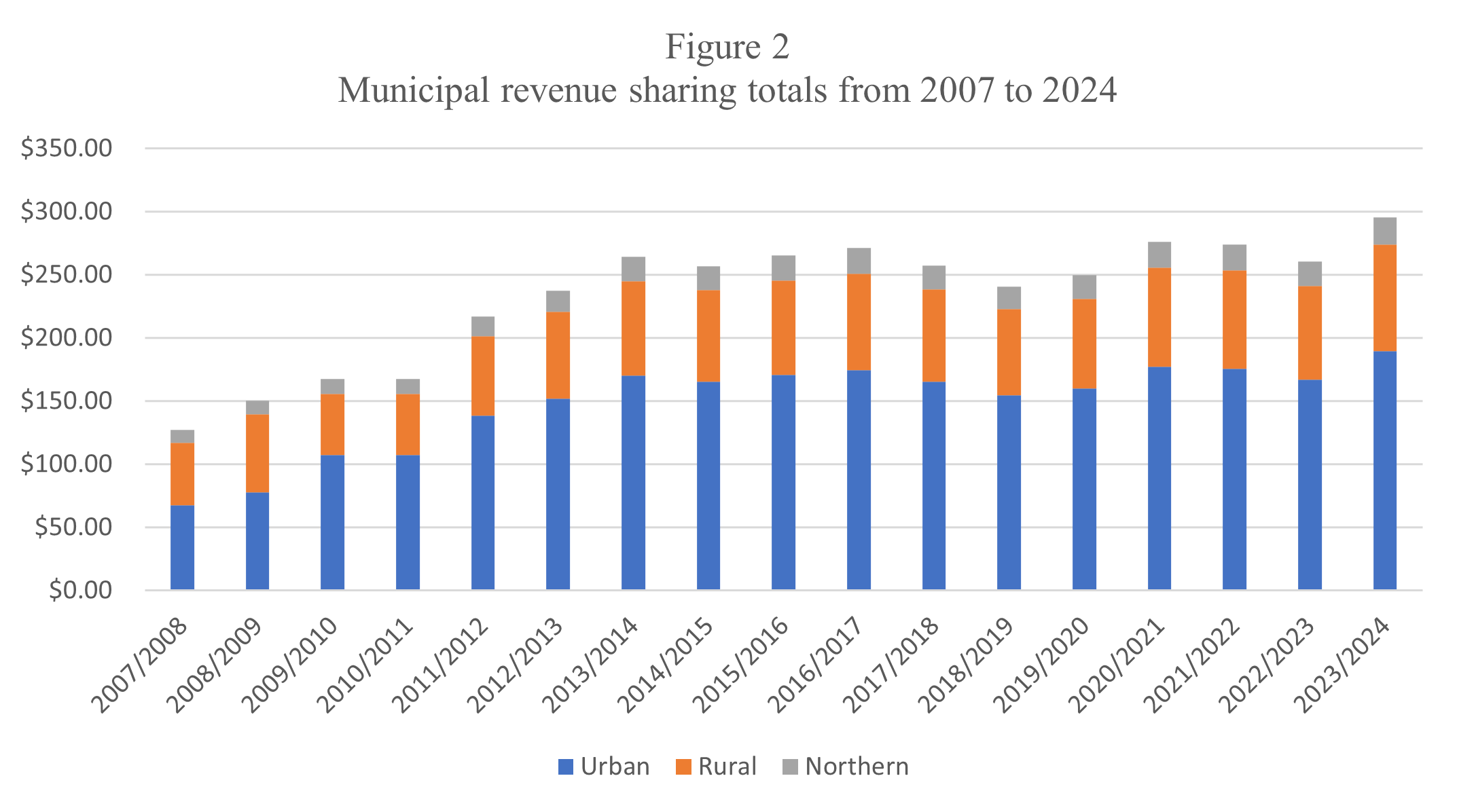

In 2006, the Saskatchewan government established a municipal sector funding agreement called Municipal Revenue Sharing (MRS). This funding agreement, unique in Canada at the time, offered municipalities predictable and sustainable annual funding. In 2009, the Saskatchewan government solidified the MRS with a simple formula: 1% of Provincial Sales Tax (PST) revenues were dedicated to the MRS pool, which was then divided among all municipalities in Saskatchewan. This funding for Saskatchewan municipalities provides sustainable and predictable funding that the sector can use with no strings attached. The funds can be used at the local council's discretion based on locally established priorities. The government changed the formula during the 2017 provincial budget by reducing it to .75 % of 1% of the PST; however, it also increased the PST pool by removing various exemptions, which kept the MRS allocation roughly the same. In 2023, municipalities in Saskatchewan received a per capita share total fund of nearly $296 million. Figure 2 provides an overview of the municipal revenue sharing program funding year over year since 2007.

As previously stated, municipalities own and maintain over 60% of public infrastructure in Canada but receive only 8-10 cents of every tax dollar collected. This creates a significant funding gap for building, upgrading, and maintaining the infrastructure necessary to support population growth and economic development despite receiving GTF and MRS from other levels of government. The current framework does not allow municipalities to allocate funds according to local priorities, limiting their ability to respond effectively to pressing issues such as aging infrastructure, increased public safety, and climate change.

The financial burden is worsened by provincial and territorial governments frequently imposing additional responsibilities on municipalities without providing adequate funding. This transfer of services increases economic pressure on municipalities, which must find ways to finance these services within their limited revenue options. Rural, northern, and remote municipalities face distinct challenges like smaller tax bases and higher infrastructure costs. Discussions have taken place within the sector, suggesting that a review of municipal, provincial, and federal government responsibilities may be necessary, encouraging a more comprehensive understanding of the existing disparities in the fiscal framework and insufficient support for these communities. In summary, the outdated fiscal framework hampers municipalities' ability to generate sufficient revenue, invest in essential infrastructure, and deliver critical services, thereby limiting their capacity to promote sustainable growth and enhance the quality of life for their residents.

Municipalities often face political and public resistance to adjusting property tax rates, making responding to changing financial needs or unexpected expenses challenging. Higher property taxes can also increase housing costs, making it more difficult for residents to afford homes.

This is particularly problematic during times of housing shortages and affordability crises. As municipalities reluctantly take on more responsibilities, such as public transit, climate change adaptation, and social services, more than the revenue from property taxes alone is needed to cover these expanding needs. Quite simply, property taxes were never designed to address these additional responsibilities. The reliance on property taxes forces municipalities to make difficult budgetary decisions, often leading to deferred maintenance and underinvestment in critical infrastructure. This can result in long-term financial challenges and deteriorating public assets. Municipalities' overreliance on property taxes limits their capacity to invest in local priorities and innovative solutions. A more diversified and flexible revenue framework is essential for supporting sustainable municipal growth and effective service delivery.

In Saskatchewan, there are 774 municipalities for a population of 1.2 million. Some would argue that there are too many municipalities for this small population. It begs the question of whether there should be a move by the provincial government to restructure the municipal sector. I conducted a literature review on amalgamation in my research project titled The Sustainability of Saskatchewan Municipalities (2024). I reviewed studies from around the world, including Canada, and discussed how central governments have addressed the challenges in their municipal sector. The review also focused on how central governments rationalized their municipal industry to ensure efficiency. I found in this literature review that central governments have recognized that the municipal sector amalgamation is only one of the solutions to ensuring municipal sector efficiency. Some central governments have embarked on an amalgamation journey in their local governments, while others have moved away from amalgamated communities and de-amalgamated them. In Australia, the central government embarked on a journey of amalgamation.

In contrast, the State of California journeyed in the opposite direction with the de-amalgamation of portions of the City of Los Angeles. The State of California argued that the city of Angels was too big and needed to restructure the administrative structure to gain more efficiencies. Whether studies originated in Europe, the United States, or the South Pacific, there is no one-size-fits-all. Local realities and the magnitude of local governments' challenges should drive the establishment of the correct municipal sector model.

The review of Canada’s approach to municipal amalgamations yielded observations like those from my global review. In the late 1990s, Ontario experienced a significant amalgamation of its municipal sector, which did not produce substantial efficiencies. Local leaders encountered further challenges post-amalgamation, such as rising operational costs. In Québec, after the PQ government mandated amalgamations within the municipal sector, a change in central government fostered an environment where municipalities could opt to de-amalgamate, and many chose to return to their original structures. The Québec Liberal party contended that the decision to amalgamate should rest not with the central government but local leaders. Once again, no single model for a sustainable municipal sector has emerged globally, including in Canada. The literature review indicates that addressing and tailoring solutions to local realities is appropriate for municipal government efficiency issues.

Proposed solutions

In its recent publication, "Making Canada’s Growth a Success: The Case for a Municipal Growth Framework,” the Federation of Canadian Municipalities (FCM) proposed solutions to address municipalities' challenges.

First, there is a call to modernize municipal funding by increasing direct annual transfers to municipalities, linking these transfers to economic growth, and indexing them to the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Additionally, broadening the eligible expenses under federal transfers to include operating and capital costs will enable municipalities to address local priorities more effectively.

Second, diversifying revenue sources is crucial. This could involve allocating a portion of income taxes to municipalities, permitting them to levy new taxes or user fees, such as taxes on vacant dwellings, and reducing the provincial portion of the property tax to create more property taxation room.

Third, a comprehensive plan to end chronic homelessness is needed, which would establish a coordinated federal, provincial/territorial, and municipal approach with clear roles and responsibilities. This plan should increase investment in non-market and supportive housing through a Housing First method and implement measures to prevent individuals from becoming homeless.

Fourth, long-term and predictable funding for infrastructure projects is essential, along with support for municipalities in maintaining and upgrading existing infrastructure to accommodate growing populations. In recent years, municipalities have implemented more robust municipal asset management. Asset management is crucial for several reasons, as it involves the systematic process of efficiently maintaining, upgrading, and operating municipal assets. Therefore, not having long-term and predictable funding makes asset management much more difficult.

Regarding climate change, providing adequate funding for municipalities to adapt and investing in green and grey infrastructure will help ensure community resilience while supporting local climate action plans to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Improving public safety is another priority, requiring municipalities to have the resources to address the increasing costs of policing and emergency services while promoting collaboration among various levels of government.

Support for urban, rural, northern, and remote municipalities and communities is also essential. This will ensure that funding models adequately reflect their unique needs and address their infrastructure deficits. Lastly, streamlining administrative processes by simplifying the application for government grants and transfers will help reduce the burden on municipalities, particularly smaller ones with limited staff. By implementing these solutions, municipalities can better meet the needs of their residents, support sustainable growth, and improve the quality of life in their communities.

These measures, as proposed, primarily aim to engage the federal government to enhance the existing CCBF (formerly known as the Gas Tax Fund). In Saskatchewan, municipalities benefit from a unique funding stream from the provincial government that others in different jurisdictions still seek. However, it’s essential to recognize that infrastructure funding must be streamlined at provincial and federal levels. Our small communities in Saskatchewan require access to infrastructure investments with minimal bureaucracy.

Jean-Marc Nadeau

Jean-Marc Nadeau is a retired Royal Canadian Mounted Police commissioned officer. In 2013, following a 23-year career in law enforcement, Jean-Marc embarked on a career in the municipal sector. As SUMA's CEO, Jean-Marc is responsible for leading and managing the organization according to the strategic direction set by the Board of Directors. He is passionate about serving the interests of Saskatchewan's urban municipalities and advancing their collective vision.

Jean-Marc holds a PhD from Johnson Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy (JSGS). His research interests include historical institutionalism in the public sector.