Economic Development in Saskatchewan: Where to from here?

The health of the Saskatchewan economy is an issue of active debate, usually leading to a discussion on how to improve the province’s economic growth and employment performance. There is often little or no agreement on either topic. The slowdown in Saskatchewan’s economic growth over the past decade demands that a more informed and inclusive discussion occurs.

By Ron Styles, Executive-in-Residence, Johnson Shoyama Graduate School of Public PolicyDownload the JSGS Policy Brief

Download the Discussion Questions

Traditionally in Saskatchewan, population growth and unemployment have been seen as the key measures determining the health of the province’s economy. Based on those two factors, it is reasonable to assume that for the past two decades, Saskatchewan’s economy has performed well. The province’s population has grown from 996,000 to more than 1.2 million, an increase of about 200,000 or 20 percent, the fastest growth since the first two decades of the 20th century. At the same time Saskatchewan’s unemployment rate today hovers at five percent, below what it was 20 years ago, ranking as the third lowest among provinces in Canada. But when you dig deeper into the economic statistics, particularly in more recent years, a less positive picture emerges.

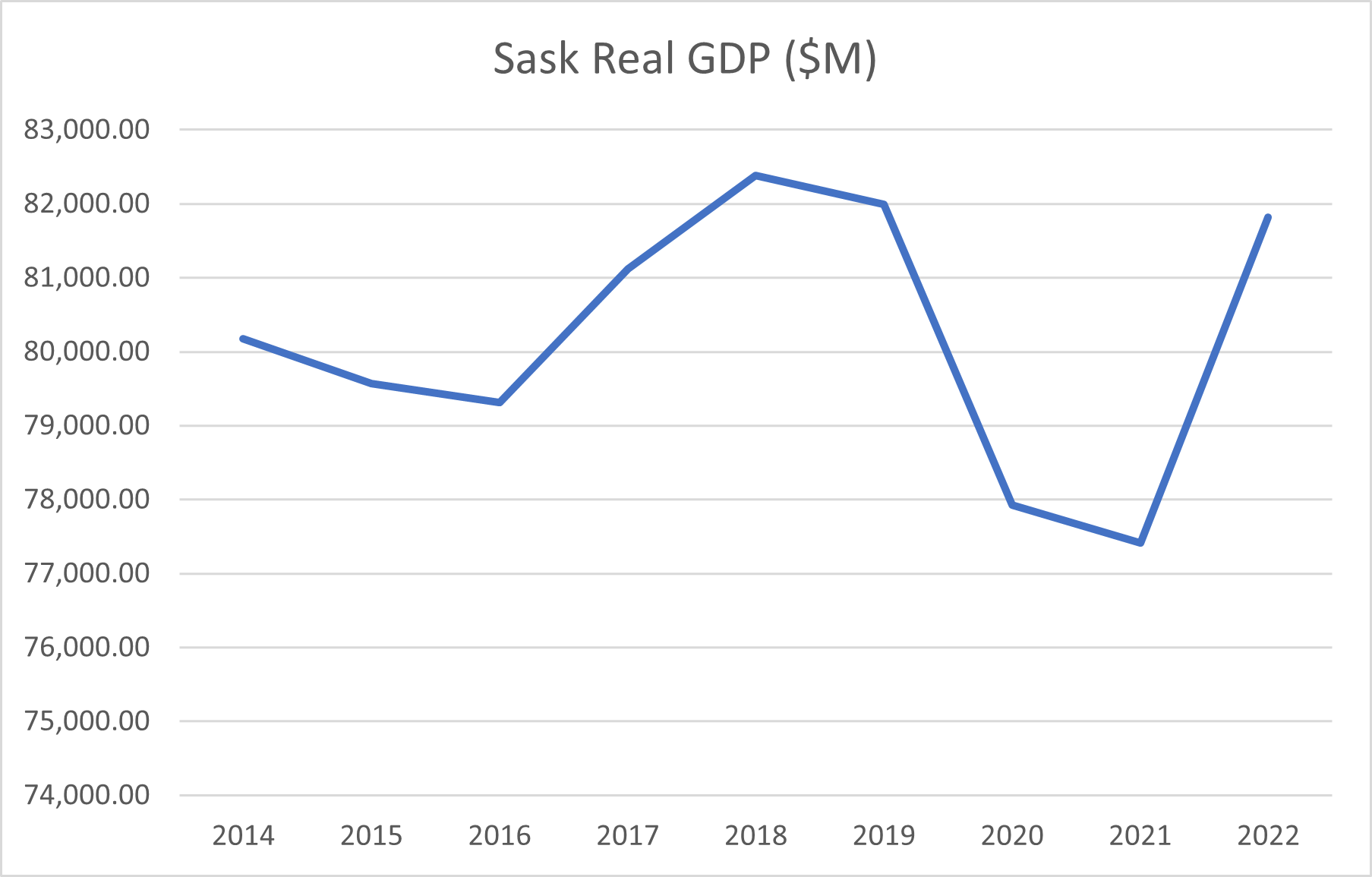

Source: Statistics Canada Table: 36-10-0402-01

The facts are that after a decade of relatively low economic growth and five years of almost no economic growth, the province is facing a challenging economic future. Saskatchewan’s Real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2018 reached $82,387M, but in 2022 was only $81,128M. In five of the last nine years, Saskatchewan has experienced negative economic growth.

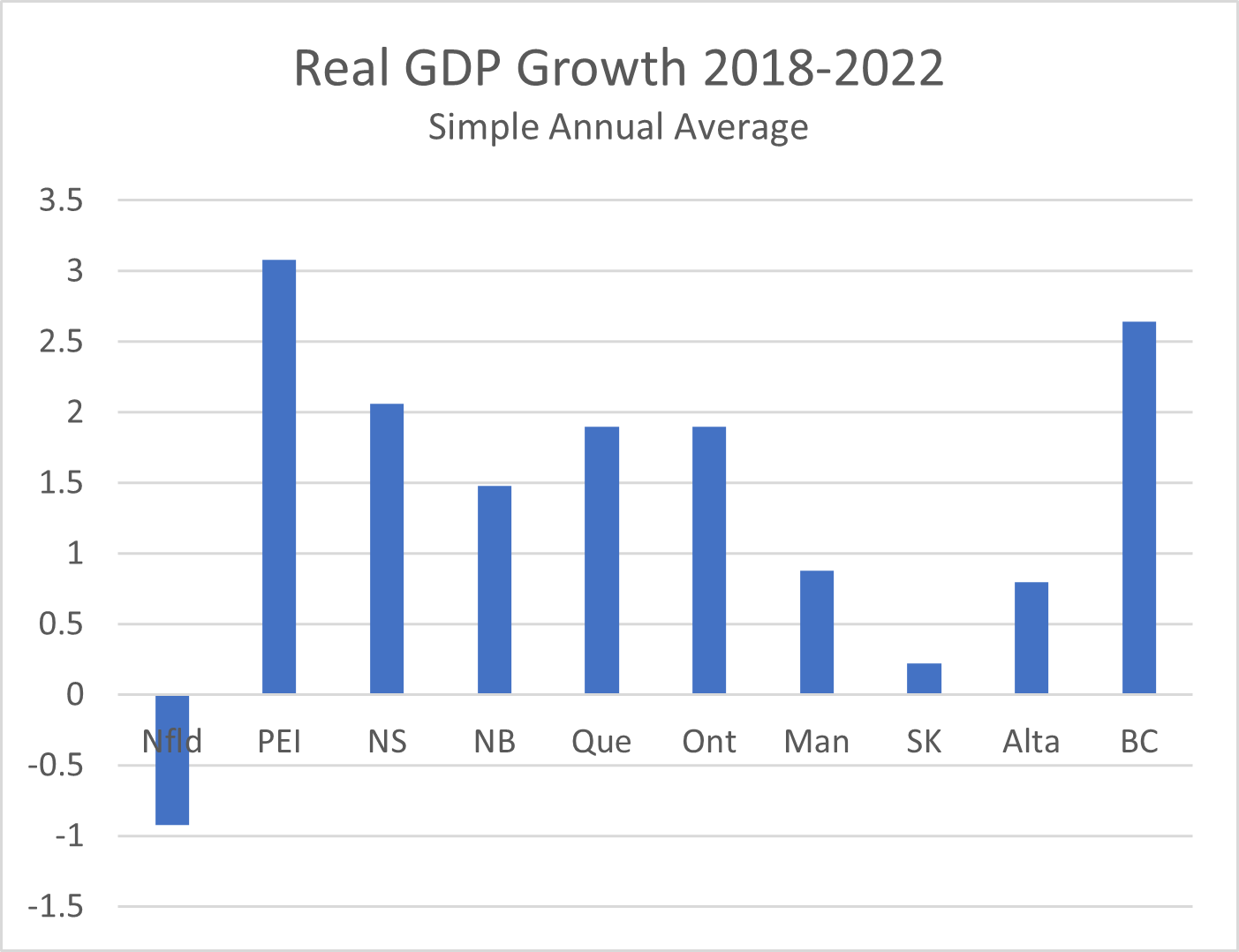

Some might believe that the impacts of the pandemic are the reason for Saskatchewan’s poor economic performance. But looking at provincial economic performance across Canada suggests otherwise.

On a comparative basis, every province but one has outperformed Saskatchewan when it comes to economic growth (Real GDP) over the past five years.

Source: Statistics Canada Tables: 36-10-0402-01 and 36-10-0434-03

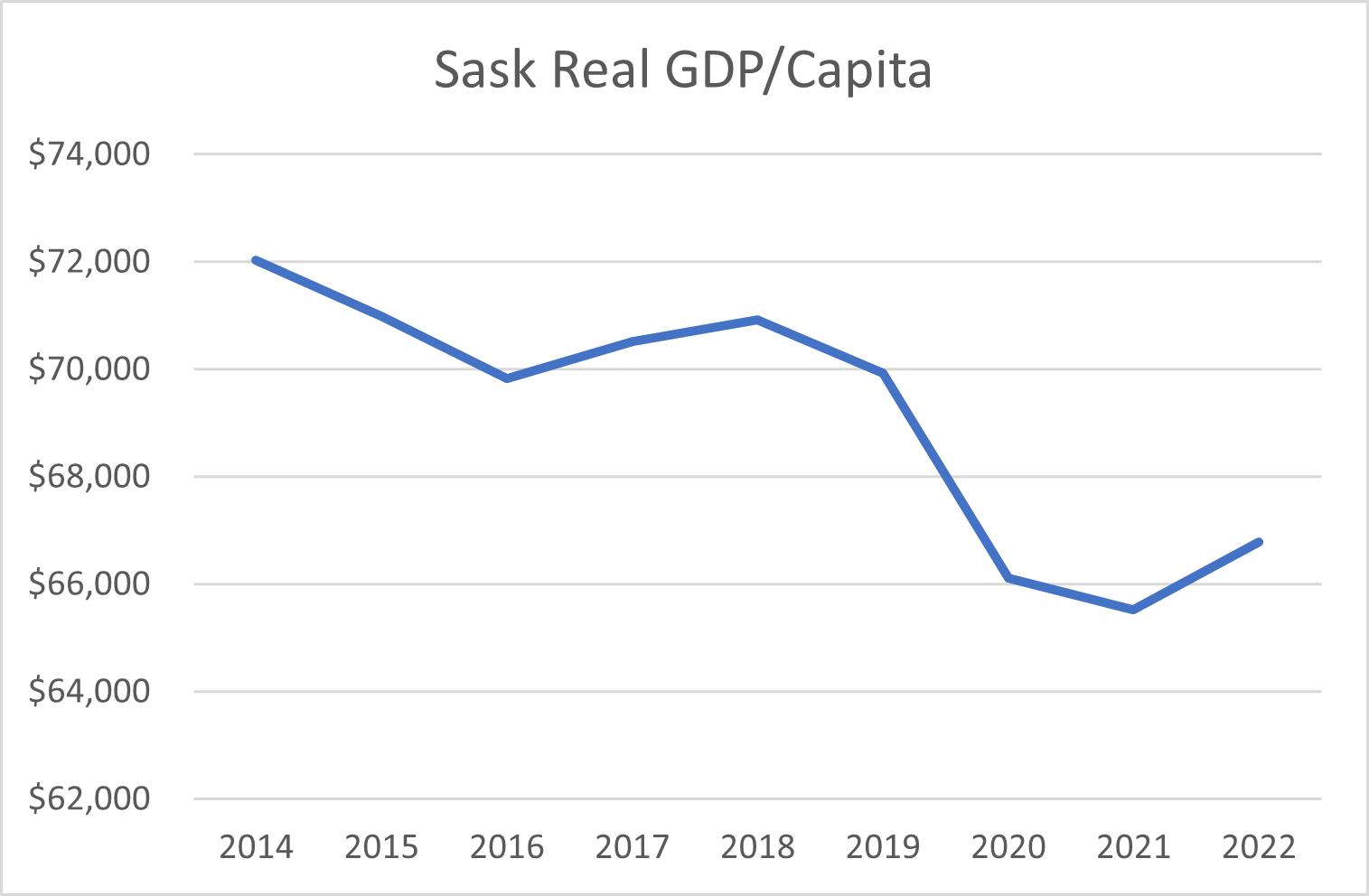

The situation is even more concerning if you look at the measure of prosperity most often used by economists – real gross domestic product per capita, which is used as a proxy for standard of living. While Canada has been unable to generate a level of growth in our real GDP per capita similar to the United States due to lagging productivity growth, there has been growth. An examination of real gross domestic product per capita shows however that Saskatchewan has suffered a reduction in our “prosperity” over the past nine years, such that today the province has a standard of living that is essentially less than it was just five years ago.

Source: Statistics Canada Tables: 36-10-0402-01 and 36-10-0402-01

Source: Statistics Canada Tables: 36-10-0402-01 and 36-10-0402-01

To put that in practical terms, the province needs to restore a level of economic growth that will allow younger people entering the workforce to find jobs in Saskatchewan, which in turn provides the tax revenue to support the services that the public expects, and the wealth to allow the province and its economy to adapt to the challenges it faces.

If Saskatchewan is to improve its economic position within Canada, it will need to generate economic growth that exceeds that of other provinces or Saskatchewan or it will be left behind and return to the have-not status characterized by equalization payments from the federal government.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine provided a temporary boost to the provincial economy in 2022, in the form of higher potash and oil prices resulting from a shut in or shut out of portions of the world market due to sanctions on Russia. However, the war will eventually end, and Russian commodities will return to the world markets. It’s likely that commodity prices will fall once that happens.

Agricultural commodities have faced a similar situation. Prices for wheat, canola, oats, etc. all increased as Ukrainian production fell, and challenges were experienced in moving their agricultural products to the world markets.

These disturbances in the world markets were key to the Saskatchewan economy rebounding in 2022 with 5.7% real GDP growth.

However, commodity prices in 2023 are already showing reductions from their 2022 highs. The provincial government forecast in its 2023/24 budget that the price of potash (mine netback, C$/K2O tonne) will fall by 32% and oil (WTI) by 12%.

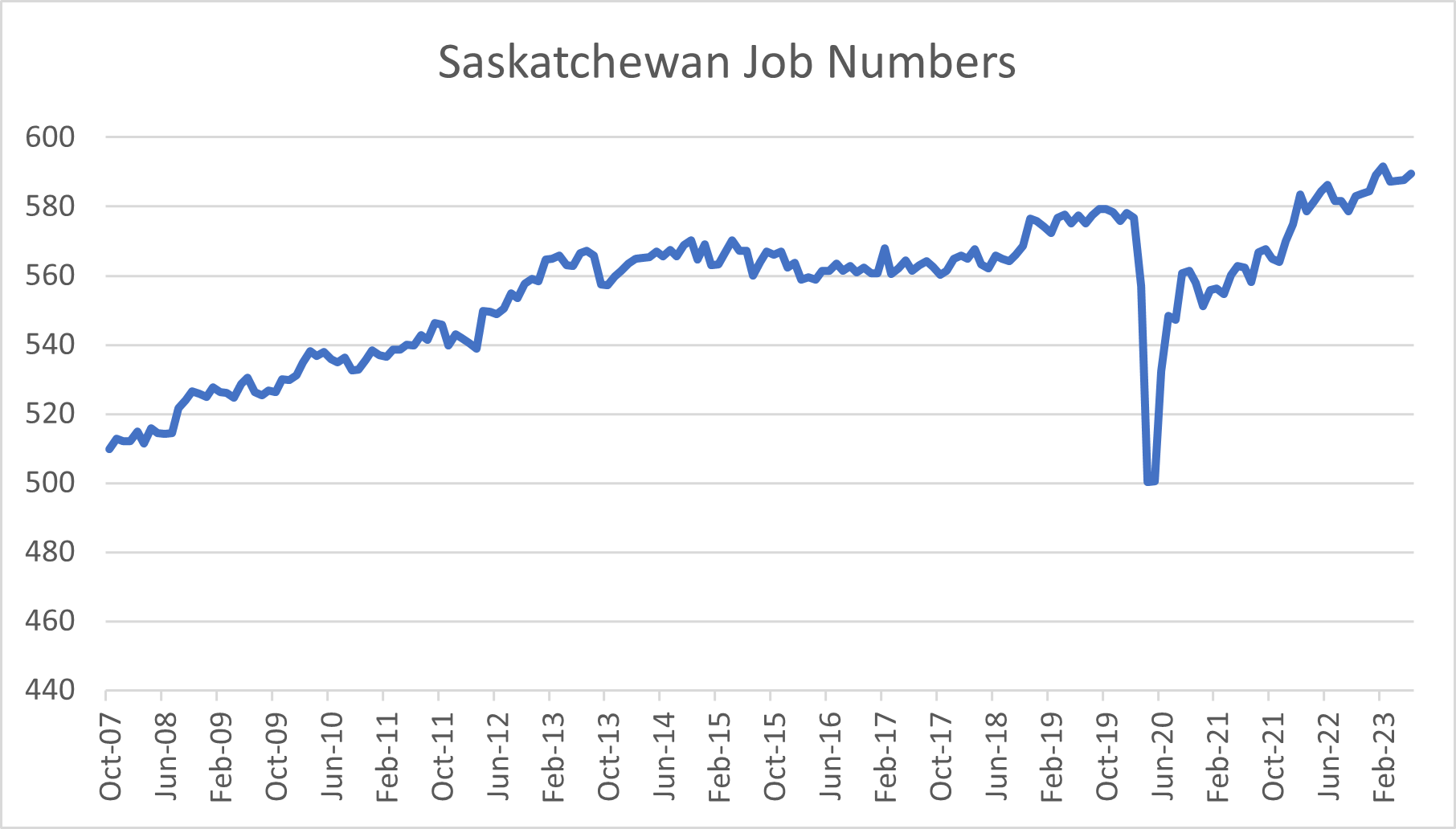

As important perhaps, is that the number of jobs in Saskatchewan has grown very little since October 2014 when it hit a high of 570,200, then plateaued for several years, hit a new high of 574,600 in late 2018 and today (June 2023) sits at only 589,500 jobs. In total, the province has only added roughly 20,000 jobs over the last eight years. During the previous five years (2008-2012) more than 50,000 jobs were created in Saskatchewan.

Source: Statistics Canada Table : 14-10-0287-01

Source: Statistics Canada Table : 14-10-0287-01

A Changing Economic Structure

What is particularly significant is that during the past five years, the structure of our economy has also changed. The pandemic together with other trends and an alternative economic development focus has resulted in seven of the 20 economic sectors in Saskatchewan declining in real economic size.

Several sectors have experienced significant reductions in economic activity, including construction, transportation, and warehousing, as well as the management of companies and enterprises. Two of the categories that showed a significant decline over the past five years are the arts/ entertainment/recreation and the accommodation/food services industries. These were the sectors most impacted by the pandemic. However, other provinces have rebounded to pre-pandemic levels while in Saskatchewan that hasn’t occurred.

The lack of economic growth in Saskatchewan may have permanently impacted the post-pandemic demand for these services in addition to which inflation, especially food inflation, has reduced margins and caused some changes in consumer spending patterns.

The Saskatchewan Government’s focus on the three Fs alone, namely, food, fuel, and fertilizer – has not created the economic growth over the past five years that might have been expected.

Change in Saskatchewan Econ Sectors: Real GDP 2018 to 2022

Source: Statistics Canada Tables: 36-10-0402-01

| Sector | $M | %Change |

| Agriculture, forestry, fishing, and hunting | -213.90 | -3.06 |

| Mining, quarrying, and oil and gas extraction | -644.40 | -2.93 |

| Utilities | 50.3 | 2.84 |

| Construction | -1263.70 | 20.74 |

| Mnaufacturing | 411.90 | 8.67 |

| Wholesale Trade | 245.70 | 6.50 |

| Retail Trade | 266.40 | 8.14 |

| Transportation and warehousing | -280.60 | -7.29 |

| Information and cultural industries | 54.10 | 4.33 |

| Finance and insurance | 487.90 | 18.72 |

| Real estate and rental and leasing | 569.90 | 7.61 |

| Professional, scientific, and technical services | 162.30 | 10.50 |

| Management of companies and enterprises | -178.50 | -78.57 |

| Administrative and support, waste management and remediation services | -102.80 | -11.64 |

| Educational services | 286.10 | 8.30 |

| Health care and social assistance | 445.30 | 9.95 |

| Arts, entertainment, and recreation | -110.20 | -25.69 |

| Accommodation and food services | -100.80 | -8.83 |

| Other services (except public administration) | 120.50 | 10.17 |

| Public administration | 358.40 | 9.04 |

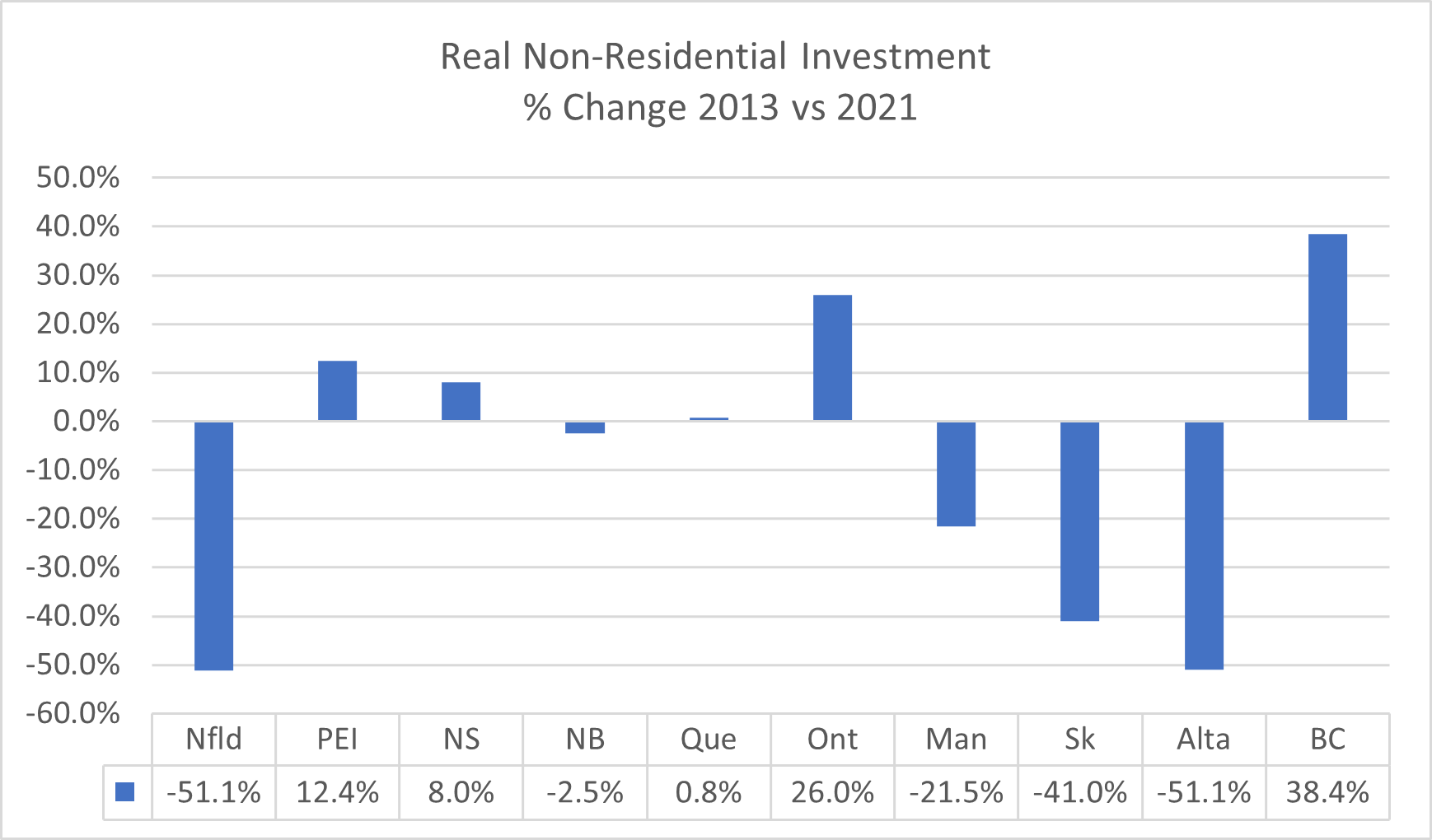

Capital Investment in Saskatchewan

The direction of an economy in terms of its absolute growth as well as its growth per capita is in part, dictated by the amount of non-residential investment in the economy. It is this investment that’s key to increasing productive capacity and growth in the province's economy. To assess whether investment in an economy is growing or contracting, it is important that the impact of inflation be removed so that the value of non-residential investments is comparable over time.

Source: Statistics Canada Table: 36-10-0096-01

Source: Statistics Canada Table: 36-10-0096-01

When the 2022 real non-residential Investment statistics are released in November of 2023, it is likely that both Saskatchewan and Alberta will see some growth compared to 2021 due to high commodity prices. However, between 2013 and 2021, real non-residential investment in Saskatchewan declined sharply by 41%, which suggests that our economy is not growing, in part due to the lack of investment.

The single largest non-residential investment in Saskatchewan today is the BHP potash mine being built near Jansen, Saskatchewan. The first phase of this mine is projected to be completed in 2026, and currently, there are very few large capital projects that are projected to start construction in the next few years. Thus, a further drop in non-residential investment in our economy appears imminent.

Out with the New and in with the Old?

For Saskatchewan to improve its economic growth and job creation, it will be important to build on the province’s strengths by focusing on the following areas:

- Diversification

- Stakeholder participation

- Multi-nationals

- Government intervention

- Immigration

- Education

- Indigenous engagement

Diversification

Saskatchewan’s economy has always been tied to commodities, which form the economic foundation upon which to build. However, in the 1970s and 1980s successive Saskatchewan governments, both NDP and Progressive Conservative, recognized it was important to aggressively pursue diversification of our economy to provide stability in relation to jobs, economic growth, and provincial finances.

This objective formed the backbone of provincial economic policy. The debate over its success can be best answered by looking at a narrowing of the swings in the gross domestic product as well as the job growth that came from that focus.

Stakeholder Participation

By definition, the residents of Saskatchewan all have a stake in the economy, as is the case in all jurisdictions. Citizens work in and buy from the local economy and their ideas and actions are the lifeblood of the economy.

That means to rebuild the economy’s institutional framework, it is critical that everyone is involved in the development of policies, programs, and investment attraction. All stakeholders, all regions, all levels of government, and all sectors of the economy should be engaged to work in partnership with the provincial government, to grow our economy.

Our Multi-Nationals

Saskatchewan has always had a mixed relationship with the largest economic players in Saskatchewan, whether it was the oil and gas industry, the mining industry, or our largest agriculture players. As the world has moved to an increasingly global economy, the ownership, management, and location of those entities has also moved outside Saskatchewan. A trend that has resulted in commercial relationships with the province, but not community relationships.

In that context, expectations for how these corporations engage with the province, beyond simply as a commercial enterprise, need to change. Companies, particularly large multinationals that operate in the province, should not be allowed to function simply on a commercial basis when they are accessing to provincial resources. A caveat needs to be added to the agreements that allow these companies to extract provincial non-renewable resources, requiring the senior leaders to actively participate in both the development and execution of the provincial government’s economic development strategy. They need to become partners in growing the province, not just in their specific line of business, but in helping to open the door to new opportunities through their contacts, their networks, and their understanding of the world economy.

This new relationship could also include a requirement that corporate services be maintained in Saskatchewan as part of their license to access the province’s resources. Between 2018 and 2022, that portion of the Saskatchewan economy categorized as the Management of Companies and Enterprises fell by 78.6%. Locating corporate services in other parts of Canada may reduce the cost of business but it does nothing with respect to growing the Saskatchewan economy.

More than ever Saskatchewan needs corporate champions who support not just their existing business operations but also advise and assist the province in attracting new economic activity.

Government Intervention

By their very nature, governments are established to intervene in the economy. They do it for all sorts of reasons using all types of policies and approaches. Over time, the types of interventions go in and out of style as the latest in public policy ideas are brought forward to meet the new and emerging economic challenges that governments face.

Saskatchewan policymakers need to return to a more pragmatic approach, one based on what works rather than a specific ideology. In today’s world, and the markets that Saskatchewan exports to and competes with, government intervention is an ongoing fact. The geo-political environment is undergoing significant shifts that are affecting trade patterns and relationships. The evidence is clear. Whether it’s the sanctions that have been implemented because of the Ukrainian/Russian War, the banning of rice exports from India as part of growing tensions between Canada and India, or the Chinese banning our canola, Saskatchewan must be prepared to use every tool at its disposal. At times that can mean government ownership when it makes sense, to ensure that Saskatchewan continues to grow its economy and improve its standard of living.

In the 1980’s, the province’s economic development strategy included passive ownership of both heavy oil upgrading facilities in Regina and Lloydminster as well as a nitrogen fertilizer plant in Belle Plaine Saskatchewan. These industrial operations are now critical components of the province’s economy and have continued to grow in output and employment opportunities.

A similar approach may be necessary to incent new areas of growth in our economy with respect to the processing of our agricultural commodities, and minerals, or to further the growth of manufacturing in Saskatchewan. The last public review by the province with respect to the processing of uranium occurred some 15 years ago. With the shift by power companies around the world to plans for both large and small modular reactors, and the demand for uranium projected to grow, it may be time to re-examine Saskatchewan’s potential to establish uranium enrichment facilities. Passive government participation in ownership may be the right policy tool to attract the necessary private sector investment into Saskatchewan.

Immigration

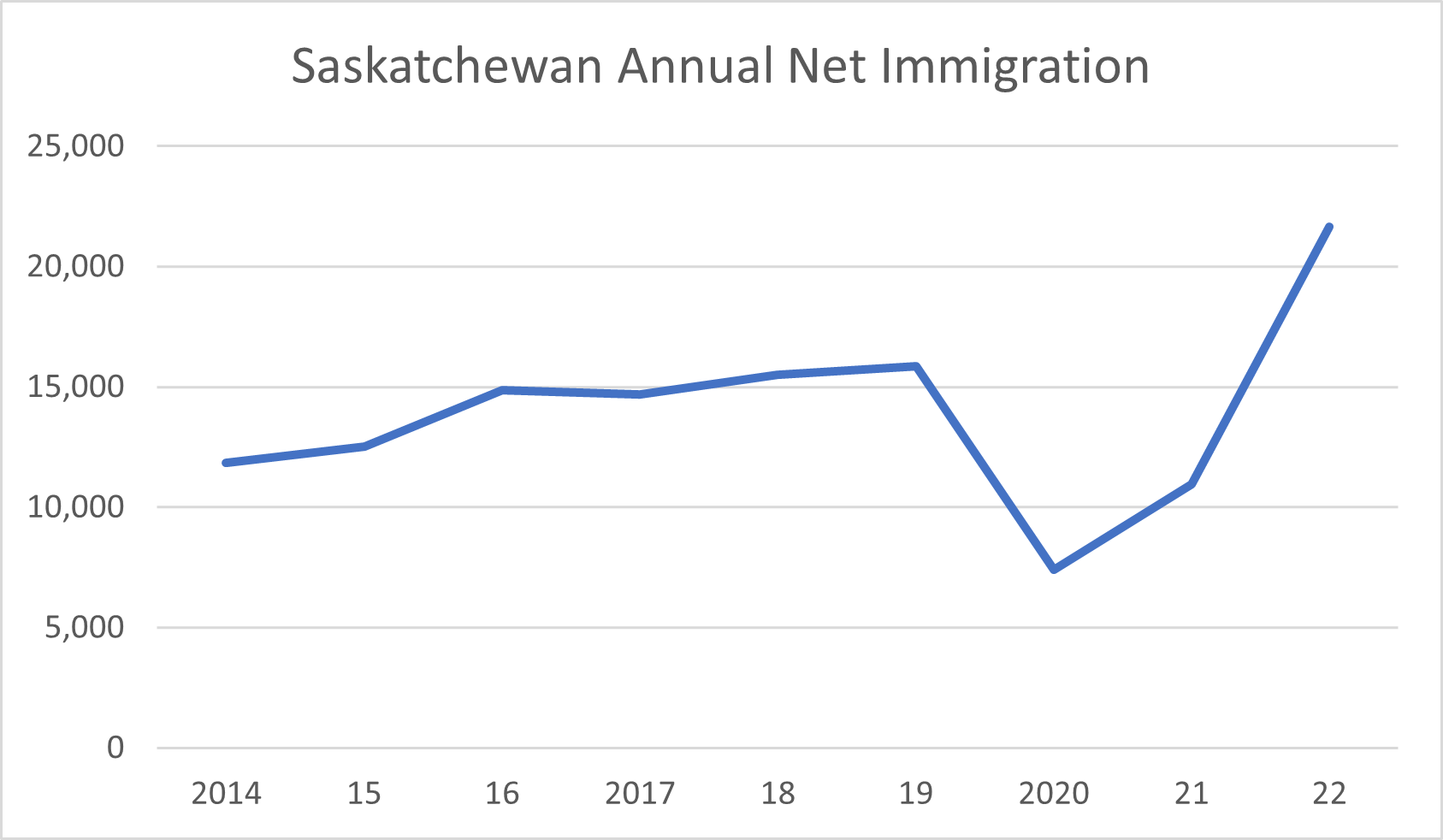

Immigration to Saskatchewan from outside Canada has grown considerably over the past decade. The province’s population has reached record levels, and the future looks bright in terms of sustaining that growth.

However, immigration needs to be supported by government policy that ensures the retention of those who were born in the province and those who have come to the province from other countries.

The retention rate for immigrants arriving in Saskatchewan in 2016 fell to 58.3% after five years compared to an 80% for those who arrived in 2011. More recent numbers indicated that the retention rate may have fallen further, with retention of immigrants arriving in 2019 falling to 67.8% after only two years in Saskatchewan. (Source: Statistics Canada Table 43-10-0018-01)

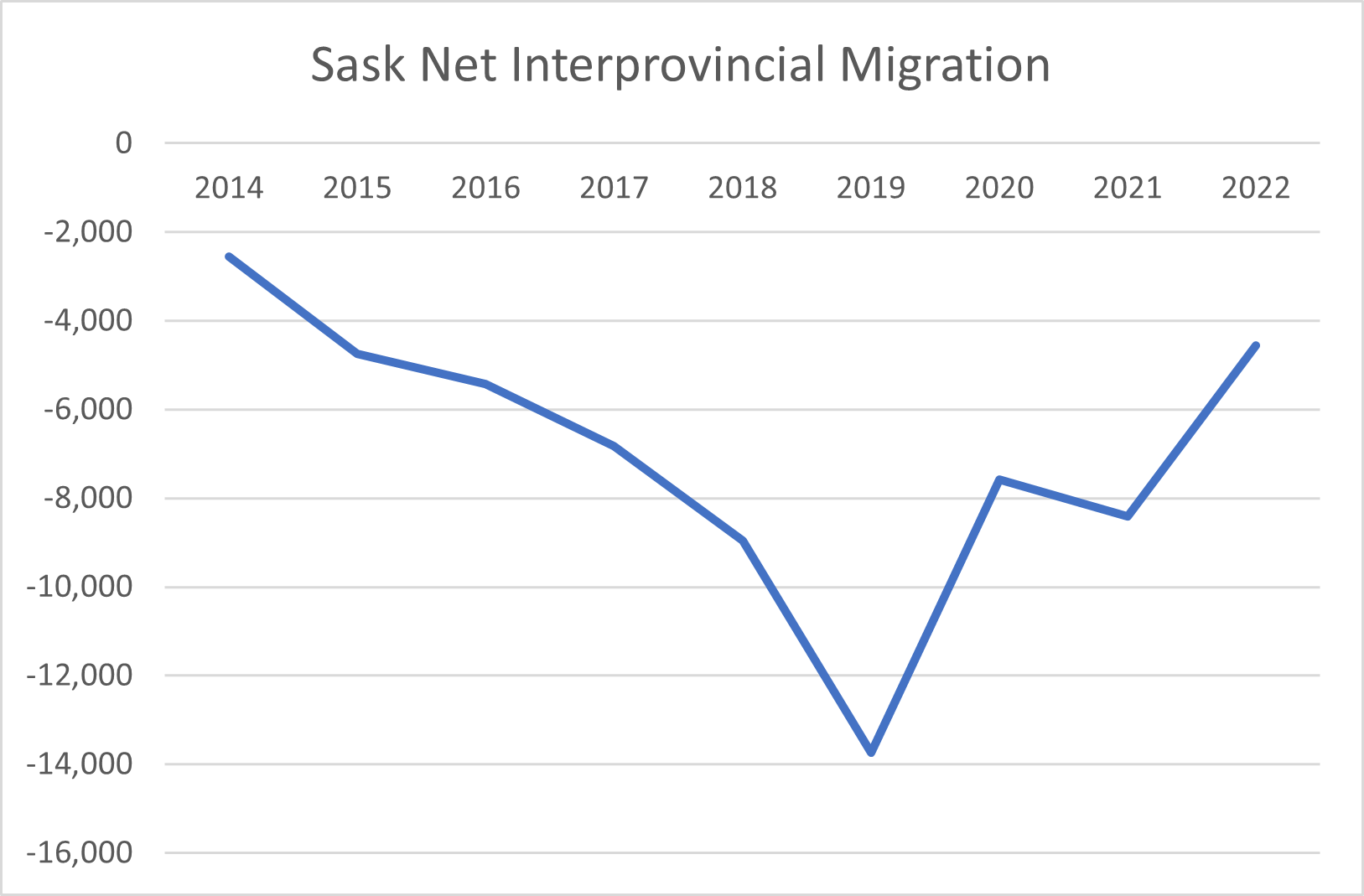

In addition, emigration from Saskatchewan to other provinces has increased to the point that beginning in 2012, Saskatchewan was losing more residents to other provinces than it was gaining. Saskatchewan is now one of only three provinces that are losing residents through interprovincial immigration on a net basis.

To continue growing the economy, the province needs to create more jobs than the number of new immigrants coming into the province. Unable to meet that requirement over the past year means the number of unemployed in Saskatchewan has increased by 26% from June 2022 to June 2023. While Saskatchewan still has an unemployment rate below the national rate, if the present trends continue, it will result in Saskatchewan’s unemployment rate exceeding the national rate, or there will be further increases in the province’s level of interprovincial out-migration.

Source: Sask Bureau of Statistics

Source: Sask Bureau of Statistics

The immigration retention rate has a lot to do with employment opportunities. But there is also the question of whether the province is supporting new immigrants to build the attachments that will ensure they choose Saskatchewan as their permanent home. In addition to jobs, they require the necessary support from Government including language classes, access to health care, technical education opportunities and access to affordable housing. A number of these needs are currently in short supply in Saskatchewan and must be addressed if immigrant retention rates are to improve.

Source: Sask Bureau of Statistics

Source: Sask Bureau of Statistics

Education

The mismatch between the available jobs and the Saskatchewan labour force has never seemed more problematic than it is today. During the spring of 2023, the government indicated there were over 22,000 unfilled jobs in December of 2022 based on its available data, yet unemployment continues to climb in the province. With international immigration into the province growing over the past few years and high school graduation rates for Indigenous students continuing to remain lower than for the remainder of the population, education is going to continue to be a key enabler of economic growth.

In addition to the development of new policies and strategies to improve the linkages between the education sector and the economy, the Government needs new strategies to address:

- The underfunding of Indigenous on reserve education by the Federal Government.

- The lower graduation rates for Indigenous youth who will make up an increasing proportion of our labour force in the future.

- The overcrowding and high student/teacher ratios in primary and secondary schools as a first step to improving educational outcomes.

- The utilization and renewal of post-secondary infrastructure including the synchrotron, the Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization (VIDO), and other components of the provincial research infrastructure to support existing and attract new organizations.

Jurisdictional battles regarding education do nothing to improve provincial educational outcomes. The province needs to work together with First Nations to demand improved funding from the Federal Government for on-reserve schools. But it must also be willing to consider funding within an accountability framework for those Saskatchewan youth receiving education on-reserve. Research and studies around the world have proven repeatedly that education and economic development are tightly intertwined and a focus on those linkages is an absolute necessity for improving economic development prospects over the coming decades.

Indigenous Engagement

The 2021 Census reported that 17% of Saskatchewan’s population is Indigenous. For that portion of our population aged 0-14 and 15-24, indigenous youth comprise 26.8% and 24.3% respectively of those age categories. Those two age cohorts combined are essentially Saskatchewan’s future labour force.

A recent population projection by Statistics Canada shows that Saskatchewan’s Indigenous population will grow to more than 18% of Saskatchewan’s population by 2035/36. (Source: Statistics Canada, Table 17-10-0058-01 Components of projected population growth by projection scenario (X 1,000)

It is imperative that the province develops new approaches to engage with Indigenous people and their political organizations in Saskatchewan. Without that engagement and their meaningful participation in economic development in Saskatchewan, the province will never be able to reach its full economic potential.

Summary

Economic growth is key to improving the standard of living in any province or country.

Over the past decade, Saskatchewan’s standard of living, as measured by real GDP per capita, is lower today than it was five years ago.

The province’s present economic development strategy is now five years old, and our province’s economy has struggled to grow. Clearly, a new economic development strategy for Saskatchewan is needed, a strategy that should be developed in conjunction with all the various stakeholders in Saskatchewan without pre-conceived policy or program constraints.

Ron Styles

Ron Styles is an Executive-in-Residence with the Johnson Shoyama School of Public Policy. He has is an MA in Economics with a specialization in Public Finance from the University of Regina.

Ron was a public servant with the Government of Saskatchewan for over 35 years. Prior to retiring in 2017, he served in a variety of roles, most recently the President of SaskTel. He was also President of the Crown Investments Corporation, the Deputy Minister of Finance, as well as the Deputy Minister of Highways, the President of Sask Housing, and the President of Sask Water.

In government, he oversaw several significant restructuring initiatives, including the last major corporate tax restructuring, the Federal-Provincial-Territorial housing agreements that devolved social housing to the provinces, SaskTel’s continued shift to an internet company based on fibre optics and emerging wireless technologies. As well, he worked on the sale of the province’s financial interests in the SaskFerco Fertilizer Plant and the Regina Oil Upgrader. Ron also works as a consultant, assisting Governments, businesses, and non-profit corporations in Western Canada.