Big Banks and Competition: The Promise and Peril of Open Banking

Open Banking promises to empower consumers by giving them easy control over their financial data.

By Marc-André Pigeon, Director, Canadian Centre for the Study of Co-operatives; Assistant Professor, Johnson Shoyama Graduate School of Public PolicyEveryone loves a good story, even policymakers.

In federal policymaking circles, there is a thriller making the rounds. Improbably, the story is about banking. It has good and bad guys. It promises slick graphics, click convenience, disruption and the promise of never having to talk to another human again about your banking. It pits hard-driving millennials against stodgy Bay Street bankers. It extends into the federal Department of Finance, where until recently, policymakers imported from the Competition Bureau were leading the review of a policy idea called “Open Banking.”1 In so doing, they were pushing against a culture that favours the way things have always been in Canadian banking: solid, safe and boring.

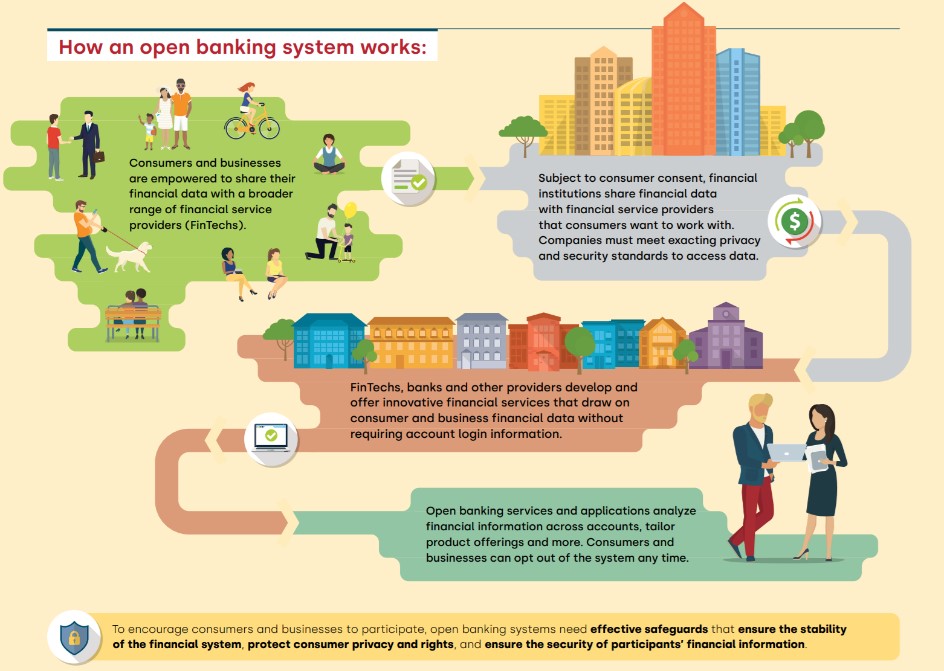

Open Banking promises to empower consumers by giving them easy control over their financial data. In doing so, it will ease the process of switching banks or comparison shopping for mortgages, credit cards or guaranteed investment certificates by simply consenting to sharing or moving their banking data. Imagine Trivago or Google, but for banking (see Figure 1). For policymakers steeped in competition culture, this is the policy holy grail. Instead of complicated rules to protect consumers from bad corporate behaviour, Open Banking promises to make it easy for consumers to exit their bank or comparison shop by clicking a button.

Figure 1: An Open Banking Journey

The idea has some powerful backers. The Senate Banking committee issued a recent report saying Canada risked “falling behind” countries like the U.K., E.U., and Australia if it failed to act “decisively.”2 Open Banking could also be the start of giving people control over all their data—utility, medical records, and more—and embedding that control in strict privacy rights and a secure digital identity. There is an air of inevitability around Open Banking and its promise to pry open a world of digital everything or, at least, competition in banking of the kind Canada has not seen since, well, forever.

Except Open Banking is unlikely to deliver on all its promises because it has to overcome regulatory inertia, an oligopolistic banking sector, and mistrust. Canada’s institutional matrix just isn’t set up to allow the radical change promised by Open Banking advocates. Just like any good story, the Open Banking narrative has some truth, some exaggeration, and some wishful thinking.

The promise of open banking

In a trilogy of books popular among bankers called Bank 2.0, Bank 3.0, and Bank 4.0, Brett King has been predicting the end of banking as we know it for 10 years. No more cash, no more branch-banking, no more loan officers, no more clunky online interfaces, no more humans, or not many anyway. Like Uber’s disruption of the taxi business, financial technology (Fintechs) firms will displace slow-moving Big Banks by removing the frictions that can make banking complicated, frustrating, slow, and expensive. And if the Fintechs won’t do it, then maybe Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Netflix or Google might. Failing that, Chinese firms like Ant Financial or Tencent Holdings will step in.

King writes: “the 21st Century bank account is not a physical artifact that consumers or small businesses will need to get from a branch, it’s just a piece of utility that will be engineered into their world through technology.”3 Book contributor Brian Roemmele, from a company called Voice-First, sees a future where people will have personal artificial intelligence (AI) bankers: “there is no chance that you would want to contemplate a world without it. There’s also no reason to go to a branch to speak to a human either.”4

But left unsaid is the matter of trust: Where does the Al banker come from? Whose interests does the AI banker serve? What if the AI banker makes an unauthorized or poorly-understood transaction? What if there is a data breach? Who watches over the AI powered by Open Banking data?

These questions underline that AI bankers only work if people are confident they will make decisions in their interest, not in the interest of a third party. They only work if there are safe and secure ways of sharing data and making payments where it is clear who is liable if something goes wrong. Because the stakes are so high, the AI banker that Roemmele characterizes as our “single most important business relationship” is unlikely to happen unless policymakers let it happen, unless they frame these considerations in policy. And that means pushing on the Open Banking door.

These kinds of policy considerations are urgent. According to Department of Finance data referenced in the Senate report, four million Canadians already share their passwords and usernames with third party service providers like Mint that “scrape” online banking information to provide a consolidated view of finances and products and use that information to pitch financial products.5 But people use these services at their peril. As the Senate reports stresses: “Having login credentials allows that third party to access the customer’s entire account and, according to the Ontario Securities Commission, may violate the terms and conditions of the customer’s accounts with their financial institutions.”

It doesn’t take much imagination to see how this can go wrong: money gets moved without consent, banks refuse to compensate for losses, depositors withdraw cash fearing more losses, and the banking system wobbles. Alternatively, AI bankers chase the best deals, causing money to slosh around the financial system like water in a bathtub and making life difficult for banks. The Senate report alludes to these “financial stability” concerns, citing the Canadian Bankers Association (CBA) which is happy to stress the importance of trust to banking. On this, the bankers have a point.

The regulatory matrix

Brett King does not so much ignore policymakers as dismiss them. He writes “policymakers have been consumed with rearview mirror mandates arising from the crisis, even as the whole world has been changing around them.”6 He adds that regulators who fail to embrace the latest in financial innovation—specifically the blockchain technology behind Bitcoin—will “by necessity” experience a situation where their “economies will start to slow.”7 From this vantage point, the latest round of international regulatory guidance (“Basel III”), born of the last crisis, is like a Maginot line. It may stop a repeat of the last crisis but the next attack will come from somewhere else.

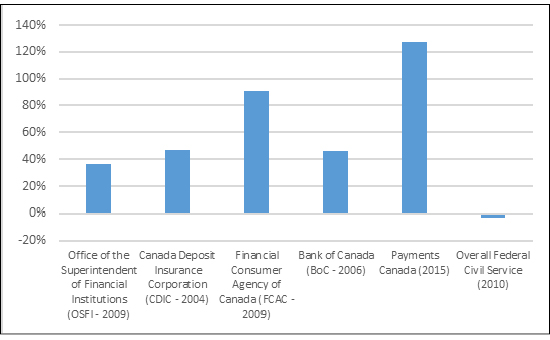

It is a well-staffed Maginot line. Figure 2 shows that since the global economy’s near collapse in 2008-09, the number of regulators employed by the federal government has grown by a third or more compared with a 3% decline in the overall federal civil service. They are the human representation of institutional inertia against radical change. On the other hand, if we take anarchist and anthropologist David Graeber’s arguments about the paradoxical pairing of “free markets” and the proliferation of “rules” seriously, these new hires may be what is needed to institutionalize and legitimize King’s vision for Bank 4.0,8 with Open Banking making it all possible. Just don’t count on any new rules displacing Canada’s Big Banks, for whom regulations represent a barrier that protects their interests against competitors.

Figure 2: Percentage Change in Employment to 2018

Returns to scale: Open banking’s unrequitable promise

The idea of applying information technology to banking is not new. Fintech has been around at least since the introduction of the automated teller machine (ATM) and online banking. But there are two things that are new. First, it only takes some programming savvy and off-the-shelf computers to develop a new Fintech application. In economics jargon, there are low technical “barriers to entry” and the promise of increasing returns to scale: once built, there are few additional costs to adding users to a software application. Second, there are large amounts of money flowing into the sector. In 2018, there was a record US$1.2 billion invested in Canadian Fintechs and US$118 globally.9

If the technical barriers to entry are low, why does the Fintech sector need so much venture capital funding? Like most digital businesses (e.g., Uber), the first challenge is customers. The more people using a service, the more valuable it is. In digital banking, there are two additional challenges. First, people worry far more about losing their money than hailing a taxi. Second, banks literally have a license to create money. Each loan or line of credit represents a new source of spending power.10 Recognizing this fact, policymakers are cautious about who gets into the business and how they operate once they are in the tent, hence the weight of regulation.

So while technological “barriers to entry” may be low, market and regulatory barriers to getting into banking are high. They are a “fixed” cost that can only be overcome with the backing of venture capital funders willing to put up with the losses that come from matching (or bettering) the price charged for services by the established banks which have already absorbed these costs and have the scale to cope with new regulatory demands.

Big dollars may not be enough. In the early Fintech days, many believed Fintech companies would displace stodgy banks weighed down by branches and clunky banking systems from the 1970s. Now, not so much. Even King concedes the point. In announcing the extension of a partnership between his Fintech company Moven and TD Bank, King noted “we realised early on that we couldn’t get tens of millions of customers using the app across multiple geographies without partners like TD, who bring us real scale and solve one of the biggest problems that fintechs face today, which is recurring revenue growth.”11

It seems people are still reluctant to leave their banks, and regulators haven’t gotten out of the way quite as much as people hoped. The promise of Open Banking is that it will fix both problems by making it easier for people to move their money and information securely in the comforting embrace of regulators. But the consumer still has to believe and the regulator has to forebear.

The peril of open banking: Humans and the limits of regulatory tolerance

The Open Banking consultation is different from most Department of Financial banking sector consultations. The 2019 consultation paper uses cartoon figures to explain the idea (see Figure 1). The Senate Banking report asks “What Open Banking Means for You,” addressing the consumer directly rather than using the agent-less passive voice typical of these reports.

The consumer focus makes sense. Almost 80 per cent of Canadians say they don’t know what Open Banking is. Those who do know, perceive it negatively12, with three quarters saying they are uninterested and need more assurances about privacy and security.13 That wariness is not unfounded. There have been some high-profile security breaches, including at banking institutions. As above, it does not take a great leap to imagine someone using login information obtained from a third-party service provider to move money out of an account. Open Banking promises to minimize that risk, or at least determine who is liable if a problem arises, but many will be reluctant to risk a loss for the marginal benefit of simpler banking services or saving a few dollars on a home loan. It only takes one bad experience for loss aversion—our tendency to weigh losses more than equivalent gains—to set in. There is also the question of whether consumers will have the time, energy and trust to use Trivago-like services to shop around for the best banking product.

If most Fintechs are now looking to partner instead of displace banks, the same is not necessarily true for the Googles and Apples of the world. They have deep relationships with Canadians and the money to acquire or develop their own Fintech offerings. No wonder then that the banking sector worries far more about this scenario than Fintech disruption. It is easy to imagine a company like Google, aided and abetted by Open Banking, offering fee-rich services and relegating banks to mere “utilities” offering low-margin highly commoditized deposit and loan products. Alternatively, they could start a bank and take-on the regulatory costs, leveraging their consumer base and Open Banking to drive out the incumbent banks.

The questions is: will they? Some are dipping their toes, including Google,14 Apple,15 and Facebook.16 But again, there are human and regulatory limits. The Facebook/Cambridge Analytica scandal has badly eroded consumer trust in social media platforms. Some 70% of Canadians say they only trust banks to manage their financial data.17 Given the centrality of banking to modern economies, regulators may not take kindly to a company like Google moving aggressively into this space, a situation already playing out in the regulatory pushback against Facebook’s promise to disrupt “money” with its Libra “currency.” Traditionally, regulators have been wary of banks acquiring non-bank businesses, recognizing that the power to create money could allow them to operate a business at a loss and drive out competitors. It is not hard to imagine regulators having similar concerns about a company like Google owning a bank.

Conclusion

There is however a deeper, more political economy reason to be skeptical about the disruptive potential of Open Banking: Canada’s banks are more woven into the institutional fabric of this country than any other sector of the economy. Despite years of policymaker efforts to increase competition, the six largest banks have held more than 90% of banking assets for almost 20 years.18 Banking assets as a share of GDP are more than 200%, higher than in the United States (although less than a number of other developed countries).19

Bank shares are a big part of our retirement plans, occupying three of the top 10 spots on the list of Canada Pension Plan Investment Board Canadian equity holdings20 and prominent positions in other Canada-focused pension and mutual funds. The people who sit on bank boards and in senior executive positions are often former regulators, politicians, and non-financial sector heavyweights and among the most interconnected in the economy. The banks help fund some of the country’s most influential think tanks like the C.D. Howe Institute. Research shows that bank boards are the most “interconnected” in the economy. In short, Open Banking is unlikely to disrupt Canada’s banks because they are too connected, too woven into the institutional fabric and because the incentives in policymaking tend towards “limiting the focus to small variations from present policy” given the state of available knowledge and unknown costs of moving to Utopian regimes.21

That does not mean Open Banking is unimportant. It should be easier to comparison shop for a home loan, to analyze banking data, and change banks. People shouldn’t have to worry about hackers or rogue AI bankers. But we shouldn’t kid ourselves that Open Banking will fix everything that’s wrong with Canada’s banking sector. Outside of the co-operatively structured credit unions, the interests of shareholders will still collide with those of consumers. AI bankers won’t be no-strings attached gifts from the heavens. They will come from somewhere and serve someone’s interests.

Unless that changes, policymakers will need to do more than give consumers power over their data and frame the responsibilities and liabilities around sharing data. They will also have to think about curbing the power of banks, addressing bank compensation practices, reforming tax policy, and much more. But that’s a different kind of disruption and a different kind of policymaking story. It is also a story for another time.

ISSN 2369-0224 (Print) ISSN 2369-0232 (Online)

References

1 The federal Department of Finance launched a consultation process on “Open Banking” in 2019 with “A Review into the Merits of Open Banking,” available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/department-finance/programs/consultations/2019/open-banking.html. In February 2020, the person leading the Open Banking policy process, formerly of the Competition Bureau, left the Department of Finance to

2 Senate Banking, Trade and Commerce Committee, “Open Banking: What it Means for You,” available at: https://sencanada.ca/en/info-page/parl-42-1/banc-open-banking/

3 King, Brett, 2018, Bank 4.0, p. 104.

4 Ibid., pp. 158-159.

5 Senate Banking, Trade and Commerce Committee, op cit., p. 10.

6 King, op cit., p. 66.

7 King, op cit., p. 69.

8 Graeber, David, 2015, Utopia of Rules.

9 Advisor’s Edge, “Canadian fintech deals hit a record in 2018,” available at: https://www.advisor.ca/news/industry-news/canadian-fintech-deals-hit-record-in-2018/. See also: https://assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/xx/pdf/2019/07/pulse-of-fintech-h1-2019.pdf

10 For an accessible discussion of this point, see Bank of England, “How is money created?” availabl at : https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/knowledgebank/how-is-money-created

11 Finextra, “Moven strikes gold with TD Bank licensing extension,” https://www.finextra.com/newsarticle/30347/moven-strikes-gold-with-td-bank-licensing-extension.

12 The Fintech sector is anxious to address this language gap, with consulting firms now stressing the importance of using terms other than “Open Banking” to describe the policy framework. While his note was being prepared for publication, federal Minister of Finance Bill Morneau released a report by an advisory committee he established after a Budget 2018 commitment to examine the open banking issue. Among other thing, the advisory committee recommended referring to “open banking” as “consumer-directed finance,” the better to address consumer concerns that the new portability of data could somehow put their money at risk. The report also strongly recommended proceeding with the creation of an open banking / consumer-directed finance legislative framework. For details, see: https://www.canada.ca/en/department-finance/programs/consultations/2019/open-banking/report.html

13 These data are from a poll for consulting firm Accenture by Leger Marketing. See: https://www.accenture.com/ca-en/company-news-release-canadians-open-banking-security-concerns

14 Google recently announced that it was partnering with a credit union and bank to offer something approximating a chequing account for example. See : https://www.reuters.com/article/google-finance/google-to-offer-checking-accounts-for-consumers-wsj-idUSL4N27T31G?feedType=RSS&feedName=companyNews

16 See https://fintechnews.ch/fintech/facebook-banking-financial-services/22073/ and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Libra_(cryptocurrency)

17 Accenture, op cit.

18 Department of Finance, “Supporting a Strong and Growing Economy: Positioning Canada’s Financial Sector for the Future,” available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/department-finance/programs/consultations/2016/federal-financial-sector-framework.html. For a discussion of some of the competition considerations tied to the “Fintech” sector, see Competition Bureau, “Technology-led innovation in the Canadian financial services sector,” available at: https://www.competitionbureau.gc.ca/eic/site/cb-bc.nsf/eng/04322.html.

19 IMF notes that Canada has “one of the largest and most developed financial systems in the world,” with financial sector assets at 626% of GDP of which banks account for the largest share. See: https://www.imf.org/~/media/Files/Publications/CR/2019/1CANEA2019003.ashx. Other sources put the weight of Canadian banking assets at more than 250% and suggest that this is the third-highest ratio in the world. See See: https://www.helgilibrary.com/indicators/bank-assets-as-of-gdp/canada/. Our own estimate, based on Statistics Canada data, puts the figure closer to 135% which, while lower than the other estimates, is five times greater than it was in 1985.

20 See Canada Pension Plan Investment Board, Canadian Publicly-Traded Equity Holdings, as of March 31, 2019, available at: http://www.cppib.com/documents/2033/Canadian-Public-Equity-Holdings-Mar2019-EN.htm.

21 Lindblom, Charles E., 1959, “The Science of “Muddling Through”,” Public Administration Quarterly, vol. 19, no. 2, p. 85. See also Pierson, Paul, 2000, “Increasing Returns, Path Dependence, and the Study of Politics,” The American Political Science Review, Vol. 94, No. 2.Marc-André Pigeon

Marc-André Pigeon is an Assistant Professor in the Johnson Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy, University of Saskatchewan campus, and the Director of the Canadian Centre for the Study of Co-operatives. He holds a PhD in Mass Communications from Carleton University and has worked in a number of economics and policy-related positions, most recently as assistant vice-president of public policy at the Canadian Credit Union Association. He has also served as interim-vice president of government relations at CCUA, as a special advisor and senior project leader at the federal Department of Finance, and as lead analyst on several federal Parliamentary committees including the House of Commons Standing Committee on Finance, the Standing Committee on Public Accounts, the Standing Committee on Banking, Trade and Commerce, and the Standing Committee on Agriculture and Forestry. Dr. Pigeon also worked as an economic researcher at the Levy Economics Institute of Bard College and started his career as a financial journalist at Bloomberg Business News.

His research interests include the study of co-operatives, behavioural economics/psychology, income distribution, money and banking, and fiscal and monetary policy.