Democracy and the Decline of Newspapers

The reality in Canada and other nations is that traditional, printed and widely circulated newspapers are in serious decline. The business model that sustained them for more than a century, and made many newspaper moguls fabulously wealthy, is no longer sustainable.

By Dale Eisler, Senior Policy Fellow, Johnson Shoyama Graduate School of Public PolicyIt’s a quote from the 18th century that resonates today. Serving as the United States representative to France from 1786-89, Thomas Jefferson was witness to the unfolding French revolution. As a student of democracy, Jefferson famously wrote that if the choice were government without newspapers, or newspapers without government, he would choose the latter.

For context, here’s the full quote:

“The people are the only censors of their governors: and even their errors will tend to keep these to the true principles of their institution. To punish these errors too severely would be to suppress the only safeguard of the public liberty. The way to prevent these irregular interpositions of the people is to give them full information of their affairs through the channel of the public papers, and to contrive that those papers should penetrate the whole mass of the people. The basis of our governments being the opinion of the people, the very first object should be to keep that right; and were it left to me to decide whether we should have a government without newspapers or newspapers without a government, I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter.”(1)

So here we are, almost two-and-half centuries later, and the relevance of Jefferson’s observation might actually be tested. The reality in Canada and other nations is that traditional, printed and widely circulated newspapers are in serious decline. The business model that sustained them for more than a century, and made many newspaper moguls fabulously wealthy, is no longer sustainable. The great disrupting influence of digital information and communications technology made ubiquitous by the Internet has undermined the commercial foundation for print media. Everywhere you look, newspapers are in retreat. Pick your measurement: Paid circulation? Shrinking; Advertising revenue from print? Evaporating; Newsroom staff? Disappearing; Long-term viability? In jeopardy. The starkest evidence is simply the number of once viable and profitable newspapers that have ceased publication.

Offering Condolences

A website appropriately named “newspaperdeathwatch.com” lists 13 major U.S. daily newspapers that have closed since 2007. The list includes the Cincinnati Post, Rocky Mountain News (Denver), Tampa Tribune, Tucson Citizen and Baltimore Examiner, plus numerous specialty papers. One other, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer ended its print publication and now has a website only. Among the Canadian casualties are the Halifax Daily News, Nanaimo Daily News and Guelph Mercury. In Montreal, La Presse ended its printed weekday publication and now only produces a weekend print edition. It maintains a digital publication on its website.

Appearing before a the House of Commons Heritage Committee last May, the CEO for Postmedia Network, Canada’s largest newspaper chain, sounded an ominous tone about the future of newspapers. "The erosion of print revenue has been dramatic. The picture is ugly and it will get uglier. You’re going to find there will be a lot more closures," Paul Godfrey said.(2) The same grim opinion was expressed by John Honderich, chair of Torstar when he appeared before the committee. “My message to you is a simple one: there is a crisis of declining good journalism across Canada and at this point we only see the situation getting worse,” Honderich said.(3)

Consolidation and rationalization in the newspaper industry are attempts to staunch the bleeding. But concentration of ownership is also not a new issue. In the 1969 the Keith Davey committee of the Senate looked at the concentration of newspapers ownership. Then, in 1981, the Kent commission investigated the growing concentration of ownership in newspapers and its effects on journalism after dailies in Ottawa and Winnipeg were shuttered as part of a bargain between two major newspaper chains. But this time, the situation is fundamentally different. It’s less about the structure of the newspaper industry and more about its very existence of traditional media and the future of journalism.

Postmedia last year purchased the competing tabloid Sun newspaper chain and subsequently announced it was merging newsrooms. As well, Postmedia has been attempting to sell portions of its real estate in an effort to help raise capital and reduce its crippling debt. The Toronto Star, once a business and journalistic powerhouse, has been hollowed out. A little more than a decade ago, Torstar’s market capitalization was $2 billion. It had plummeted to $181 million by early this year, and has continued to decline.(4) Last January, Torstar closed its printing plant in favour of contracting out its printed paper. In September, Maclean’s, Canada’s only weekly newsmagazine, announced that it was reverting to a monthly publication, which it was in the 1970s before becoming a weekly. There are many other examples of layoffs and consolidations across the industry at smaller community-based newspaper chains, such as Glacier Media, which has been shedding titles in British Columbia.

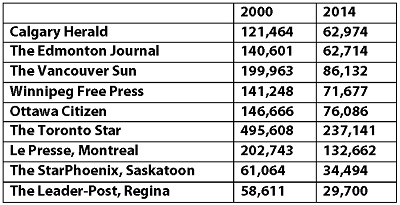

The starkest evidence of what’s happening to newspapers is the decline in paid circulation. The chart below shows a small sampling of what’s happened over 14 years in terms of paid newspaper circulation in Canada. It’s not a pretty sight. To paraphrase a newspaper publisher from the 1970s, newspapers are in the business of selling eyeballs to advertisers. Eyeballs are abandoning newspapers, taking advertisers with them.

Clearly, the newspaper industry in Canada is in dire straits. But is the public interest being harmed by a decline in good journalism as a result of a failing newspaper business model? The drop in readership of printed newspapers has been offset by the emergence of almost unlimited digital online sources of information, news and opinions. During the last 20 years, society has witnessed a fundamental change in media consumption habits, away from older, traditional mass media, to new digital sources that include blogs, Twitter, Facebook, news aggregators and literally millions of individual websites, all accessible through web browsers. What we have been witnessing is the unfolding obsolescence of the daily newspaper industry because of the instant, and often free accessibility to news and opinion offered by the Internet.

The core of the issue is not how citizens get their news, but if they have access to the type of credible information they need to be well-informed citizens. That’s the role of journalism, whether print or digital. There is no question that good online journalism exists. Ironically much of it is the result of traditional printed newspaper journalism that is either replicated online or is the source that spawns other online news and commentary. So, as newspapers die, so too does the journalism they produce. Newspapers have tried to transform their business model to fit a digital world by developing an online presence and attempting to sell online subscriptions. The problem is it hasn’t worked well, as not enough eyeballs, or advertisers, have followed. As John Temple, the former publisher of the now defunct Rocky Mountain News once said: “It’s like replacing dollars with nickels.”

The policy question this raises goes back to Jefferson’s long-ago observation. Is journalism so fundamental to the proper functioning of a democracy that the viability of the newspaper industry is a public problem in need of a public solution? If so, what form should that solution take? The currency of this issue has not been lost on those in power federally. Earlier this year, the Government of Canada asked the Ottawa-based Public Policy Forum to investigate the deteriorating state of the Canadian newspaper industry, and whether it requires a public policy response. The PPF report is expected before the end of the year.

Total Paid and Non-Paid Circulation

The Value of Good Journalism

Is the decline of print journalism a public problem? Is it about much more than the demise of an industry and extending to concern for the civics function of journalism as part of sustaining a healthy democracy? There are good reasons why government has avoided intervening in the daily newspaper sector in the past. One is that government is wary of being seen as attempting to influence a “free” press for partisan purposes by using the levers of power. The other is that there has been no economic need, as privately-owned and publicly traded newspaper companies have traditionally been very profitable enterprises. Generally, our current approach to public policy inhibits government action to prop up failing industries. The exceptions are where they are “too big to fail”, as in the case of the 2008 North American automobile and banking industry bailouts, where collapse in one sector could have economy-wide catastrophic impacts. However, if the decline of print journalism holds implications for the wellbeing of our democracy, then the newspaper business is not like just any industry. The need for a well-informed citizenry is the foundation for good governance, specifically the ability to ensure government is held accountable to its public. When newspapers close, the community loses more than just jobs, it loses a window on itself and society. Gone too is the public accountability that comes with journalistic oversight of those in government and positions of power. In his study of nationalism, Benedict Anderson sees print capitalism as the foundation for concept of “nation”. Anderson says that we live in “imagined communities” with our interests and identities linked by a common language that is reflected in the printed word. It’s in that context that newspapers define communities, the issues and interests that connect people to each other.

There is no obvious metric to judge whether democracy is being debased by the decline in newspaper readership. Voting turnout, which has been declining for decades, is one measure sometimes cited. But attributing reasons for voting behaviour with any precision is not easy. Moreover, we saw turnout increase in the last federal election, one where the Liberal party made excellent use of social media. Indeed, one can argue the sheer volume of news, commentary and information freely available online would suggest people are more informed than ever. Conversely, the availability of information does not replace the role of journalism, which is to provide not just news and information, but context, perspective, facts and analysis. With the Internet often unfiltered by journalism, it frequently becomes a trove of distortions, innuendo and outright falsehoods masquerading as legitimate news. As more and more people use the Internet as the source of information, the risk of distorted judgment and its effect on democratic choice grows. One can reasonable argue that the spectacle of the U.S. presidential election, and particularly Donald Trump’s bizarre and unconscionable campaign, is a manifestation of how public debate has been debased by the spread of half-truths, deception and outright falsehoods.Managing the Issue

If the decline of newspapers is a public problem, the question then shifts to what form a public policy response should take. On that score, several models have emerged, ranging from direct support to the industry through advertising buys and grants, to support for the creation of content and regulatory control over competition. In his appearance before the House committee, Godfrey called on government to support the newspaper and print industry by increasing its advertising, which has fallen dramatically. Evidence the federal government has abandoned newspaper advertising in favour of online platforms is contained in a March 2016 report by Canadian Heritage entitled “Newspapers in Canada: The New Reality of a Traditional Industry”. It states: “Between 2008-09 and 2014-15, the proportion of ad spending fell by 96 per cent for daily newspapers and 31 per cent for community newspapers, while increasing by 106 per cent for the Internet.” For the purposes of the issue whether government has a responsibility to support the newspapers sector because of the important journalistic function it plays in Canadian society, the report also goes on to note that there is no formal policy or framework to support the newspaper industry.

What minimal print journalism policy that exists is the responsibility of Heritage Canada. It offers support for newspapers and magazines in the form of the Canada Periodical Fund (CPF) – Aid to Publishers component, which provides financial assistance to Canadian print magazines, non-daily newspapers and digital periodicals. Its objective is: “to ensure Canadians have access to diverse Canadian editorial content of printed magazines, printed non-daily newspapers and digital periodicals.”(5) Using a formula based on eligible copies sold or circulated by verified request over a 12-month period, the Aid to Publishers program provides funding to eligible Canadian publications. Publishers are able to use funding to support the creation of content, production, distribution, online activities or business development. In 2014-15, a total of $53.4 million was given to more than 400 publications, many of them trade and lifestyle journals.(6)

Clearly, government believes there’s a role for public policy to help shape the media landscape. The most obvious example is the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. With concerns about the growing influence of U.S. radio in Canada, the CBC was established in 1936 with a mandate to deliver a national radio service for Canadians. Previously, the government had exercised control of the radio market by issuing licences to private broadcasters. Today, the CBC receives more than $1 billion a year from Ottawa to support its English and French, radio and TV operations as part of national cultural policy, with the Trudeau government expanding its support. Another major public policy tool for management of the media market is the Canadian Radio-Television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC), which “regulates and supervises broadcasting and telecommunications in the public interest.” According to its regulatory policy under the Broadcasting Act, the CRTC “takes into account regional needs and concerns; is readily adaptable to scientific and technological change; facilitates the provision of broadcasting to Canadians; and facilitates the provision of Canadian programs to Canadians.” What the CRTC does not do is have any regulatory power over the newspaper industry.

If this time is truly different, however, new policy solutions will be needed. In the digital era, the public policy question is not about newspapers per se but about ensuring good journalism that is widely accessible to the public. Clearly, newspapers are one vehicle to deliver the journalism a democracy needs, as Jefferson famously pointed out. For many, many decades, newspapers have played an integral role in helping provide the public accountability and perspective to promote a healthy democracy and good governance. Options to use tax laws, such as lowering the corporate rate on newspapers or allowing more rapid capital depreciation, are not relevant because most of the companies are losing money. Increasing the deduction for businesses that advertise in newspapers would unfairly treat other forms of advertising, including Internet-based sites that are struggling to find their fiscal feet. Government could use its own financial capacity to allocate larger amounts of its advertising dollars to newspapers, but that would also discriminate against other businesses that compete for advertising. One option is a form of negative corporate income tax, which has been considered in the past by the federal government, but never applied, to address specific sectors in distress. It would provide an internal source of financing for companies not in a taxable position by allowing newspaper companies to apply their average corporate tax rate against their losses to receive a refundable tax credit. In effect, companies would be able to monetize their losses. But there is no turning back digital technology and how it has permanently changed the way citizens get their news and information. For government to financially support newspapers that compete with other forms of media, when the public is turning away from printed newspapers, would not only be bad policy, but wouldn’t address the core issue of journalism.

Conclusion

If the objective is to ensure good journalism, the policy answer lies not with government rescuing newspapers. It’s about strengthening the existing primary policy instrument already in place to provide Canadians with the journalism they need. Specifically, that’s the CBC. There will be those who will recoil in absolute horror at the thoughts of a strengthened CBC, which they believe is already bloated, wasteful, populated with huge egos, and has an inherent bias reflected not only in programming, but its journalism. Those are not baseless criticisms, but they can also be addressed. What needs to happen is for CBC’s mandate to be changed and modernized. It must focus its resources into news and public affairs, in both TV and radio, and withdraw from drama and culture. There is no longer a need for a main CBC network dedicated to Canadian entertainment productions. The government can mandate that programming to be carried on numerous other speciality channels. Instead, the CBC should put its resources into its TV news channel and national radio service.

In a fragmented digital media universe, where people often self-select their news sources and exist in echo chambers of their own views and opinions, there is a public good in the CBC being a stronger journalistic presence, nationally and locally. A truly 24-hour, news and public affairs CBC that expands its coverage of Canada and the world, that diverts resources from its corporate bureaucracy to on-the-ground journalism , local coverage and a more robust online presence, would put the CBC at the forefront of global journalism. At the same time, CBC should no longer be allowed to compete with private broadcasters for advertising dollars. The CBC must become an instrument of journalism that is completely publicly funded and has its journalistic independence not only defended, but externally monitored to ensure all voices and perspectives are being heard in a way that reflects the diversity of the nation. In effect, it needs to be modelled after the British Broadcasting Corporation, which is recognized worldwide as an example of high quality publicly funded journalism.

Admittedly, it won’t change the grim reality for the future of newspapers, or the fact that public interest in high quality media has been eroded in a digital, Internet-based world. But that doesn’t mean there isn’t a public interest in supporting quality journalism to help provide the kind of public oversight that Jefferson long ago identified as critical to democracy.

Notes

- http://oll.libertyfund.org/quote/302

- House of Commons Heritage Committee, May 12, 2016

- Toronto Star, Sept. 29, 2016

- https://www.bloomberg.com/news/ar ticles/2016-02-17/newspapers-wither-in-canada-with-no-billionaires-to-save-them

- p. 5, Canada Periodical Fund, Aid to Publishers, Heritage Canada

- http://canada.pch.gc.ca/eng/1458569855796

Dale Eisler

Dale Eisler has an extensive background in the federal public service and Canadian journalism. After a 25-year career in journalism with Saskatchewan and national publications, Dale spent 15 years in various senior roles with the Government of Canada, most recently as Assistant Deputy Minister for the Energy Security Task Force at Natural Resources Canada. Prior to that he spent four years serving as Canada’s Consul General in Denver, CO . Before his posting in the U.S., Dale was Assistant Secretary to the federal cabinet for Communications in the Privy Council Office and began his role in Ottawa as Assistant Deputy Minister for Communications in the Finance Department. He received the 2013 Joan Atkinson Federal Public Service Award of Excellence. He is the author of three book, including “False Expectations, Politics and the Pursuit of the Saskatchewan Myth” and, most recently in 2010, the historical fiction novel “Anton, a young boy, his friend and the Russian Revolution.”

People who are passionate about public policy know that the Province of Saskatchewan has pioneered some of Canada’s major policy innovations. The two distinguished public servants after whom the school is named, Albert W. Johnson and Thomas K. Shoyama, used their practical and theoretical knowledge to challenge existing policies and practices, as well as to explore new policies and organizational forms. Earning the label, “the Greatest Generation,” they and their colleagues became part of a group of modernizers who saw government as a positive catalyst of change in post-war Canada. They created a legacy of achievement in public administration and professionalism in public service that remains a continuing inspiration for public servants in Saskatchewan and across the country. The Johnson-Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy is proud to carry on the tradition by educating students interested in and devoted to advancing public value.