Energy and the Environment: A Step Towards Reconciliation

The Government of Canada is in the midst of developing policy it hopes will help build a national consensus on what often appear to be the irreconcilable issues of energy and the environment. The effort begins from the premise that “a clean environment and strong economy can go hand-in-hand and is central to the health and well-being of Canadians.” It is a challenging, complex, inherently divisive and critical initiative.

By Dale EislerThe Government of Canada is in the midst of developing policy it hopes will help build a national consensus on what often appear to be the irreconcilable issues of energy and the environment. The effort begins from the premise that “a clean environment and strong economy can go hand-in-hand and is central to the health and well-being of Canadians.”1 It is a challenging, complex, inherently divisive and critical initiative.

In one form, a national energy strategy already exists. A year ago the provincial Premiers signed a Canadian Energy Strategy that sets out broadly shared principles and priorities. But as the effort of provinces and territories with divergent interests, and without an overarching role for the federal government, it amounts to more of an aspirational document than a strategy.

An Issue Defined by Divisions

The starting point in determining the right combination of policies to form achievable and durable policy is to acknowledge the divisions inherently part of the process. In fact, the very idea of a national strategy is itself weighted down by history. The shadow of the 1980s National Energy Policy and the national and political consequences it created extends to this day. The context has been made even more complex over the years with the advancement of Indigenous rights, the steady rise of the energy sector in the West as a major economic engine for the nation, political realignment federally that saw the demise of the former Progressive Conservative party, and the re-emergence of climate change as an important national and international issue.

There is no point in avoiding the difficult reality that a national strategy must be carved out of a daunting economic and political landscape. Nor should the possibility be ruled out that there is no reasonable path to consensus. Perhaps the most likely outcome is no outcome, and Canada continues to muddle along with an ad hoc approach that has shaped energy and environment policy to date.

The odds of little progress are very real. At stake are sectoral, regional, First Nations and national economic interests. They include federal government environmental objectives that are not always shared by all provinces, the rights of Indigenous people, the clash of federal-provincial jurisdictions, and the standard of living for millions of Canadians. Still, the mere admission of unaligned and contradictory interests is itself a small, but important step towards finding a basis for policy consensus. If everyone begins with the realization there is no perfect solution, a common objective becomes more realistic. As is often the case in forging national public policy in Canada, it requires compromise. Another way is to call it collective action in the national interest.

Of course, who defines the national interest is itself a challenge. In a federation like Canada, where there are clear constitutional divisions of powers, as well as shared areas of jurisdiction, no single voice dominates. Section 92(a) of the Canadian Constitution Act gives each province the power to “exclusively make(s) laws” regarding the “development, conservation and management” of natural resources and the power of direct taxation. For its part, the federal government controls the regulation of trade and commerce, which includes interprovincial pipelines, and has jurisdiction for matters relating to First Nations. Both orders of government share responsibility for environmental regulation. But given that the mandate for the Government of Canada is derived nationally from all regions and provinces, it clearly has the greatest moral authority when it comes to determining the national interest.

Both energy and the environment fundamentally define Canada. As a northern nation with an extreme climate and widely-dispersed population narrowly stretched across the continent, energy is critical to our standard of living and quality of life. Similarly, Canada’s vast geography, breadth and quality of its diverse environment and richness of its natural resources are part of our national identity.

All these factors create the context for trying to determine a coherent national approach on energy and the environment. Fundamental to success, therefore, is public policy that brings about reconciliation between these competing interests.

Facts That Frame the Context

To strike the right balance requires recognition of certain facts. They include:

1. On a per capita basis, Canadians are among the world’s largest consumers of energy. It is a reality shaped by our northern, variable climate, and a widely dispersed population over a massive land mass that requires far greater energy consumption than smaller, more densely populated nations.2

2. Canada has a mature, industrialized economy. “Extraction and processing of energy and non-energy resources contribute substantially to Canada’s industrial activity, and tend to be energy intensive.”3 In 2014, the energy sector accounted for 13.7 per cent of Canada’s GDP, or $254 billion. Oil and gas represented 10.6 per cent of GDP, equalling $196 billion. In terms of total employment, the energy sector employed 950,690 Canadians or 5.2 per cent of total employment. The oil and gas sector employed 4.1 per cent of employed Canadians, or 742,490 individuals.4

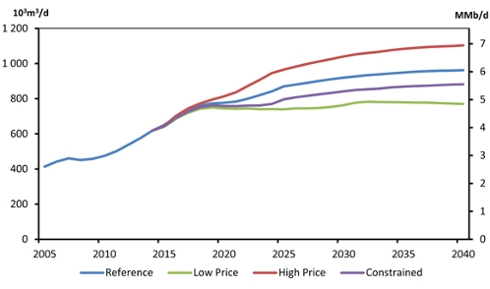

3. Global demand for oil is anticipated to grow by 12 per cent to 103 mb/d, up 13 mb/d, by 2040. Chart One forecasts western Canadian oil production to grow by 50 per cent, from approximately 4 mb/d in 2016 to 6 mb/d in 2040. In a more constrained environment production would still grow to 5.5 mb/d.5 The importance of the oil and gas sector to the national economy, coupled with global demand, means that any realistic transition to a low-carbon economy will be a slow process, extending for decades. For the foreseeable future oil production will remain an important economic engine for Canada.

4. As a signatory to the December 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change, the Government of Canada committed to reduce GHG emissions in Canada by 30 per cent from 2005 levels by 2030. Chart Two shows how aggressive the goal of 2030 is and how much emissions would have to be reduced – an absolute annual reduction of 291 megatonnes assuming current policies – to reach the 2030 goal of 524 megatonnes of GHGs. For an energy-driven society and economy like Canada, that is an ambitious and daunting policy objective. In 2013, Canada generated 18.9 per cent of its energy from renewable sources, almost 72 per cent of which came from hydro. Wind and solar combined accounted for only 2.25 per cent of the renewable energy portfolio.6

5. Committed to a “nation-to-nation” relationship with First Nations, the federal government has endorsed the United Nations Declaration on Rights for Indigenous People (UNDRIP) which provides for “free, prior and informed consent” on “matters that may affect them.” However, Justice Minister Jody Wilson-Raybould has told the Assembly of First Nations the government believes the Declaration means Indigenous people “must be able to participate in shared decision-making with other levels of government. For me, this is how free, prior and informed consent is operationalized.”7 In other words, no absolute right to determine the decision.

The line chart shows the greenhouse gas emissions and projections for the years 2005 to 2030. The line between years 2005 to 2013 shows historical emissions. Starting in 2014, the middle line represents the reference or “with current measures” scenario, and the bottom and top lines represent alternative scenarios. The Canadian targets for 2020 and 2030 are also shown (622 and 524 megatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent respectively).

These are the basic, if not all, parameters within which a national energy and environment policy must somehow fit. Recognizing the constraints they impose, and the consequences of action in each case, requires a policy with components that address each as part of building the case for national interest.

The objectives should be a strong, sustainable economy, a healthy and protected environment, a secure energy future, respect for Indigenous rights and self-determination, and a high standard of living and quality of life. Underpinning them must be recognition that none is dominant and each needs to be measured in the context of the others. In the words of Wilson-Raybould to the AFN, it must be an “evolving system of cooperative federalism and multi-level governance.”8

Public Legitimacy is the Key

So what do these objectives mean in practical policy terms? The most critical is public legitimacy. In its effort to find a path forward, the Harper government in 2012 implemented comprehensive reform of the regulatory process around major resource projects. Some of the measures made sense: the certainty created by clear beginning-to-end timelines for reviews; eliminating duplication by allowing provincial environmental reviews that were considered equivalent to preclude the need for a parallel federal process; and, limiting intervenor status at National Energy Board reviews to individuals with expertise or who were personally impacted by the proposal under review.

But those efforts ultimately were overwhelmed by the public perception of a government biased to development and Canada’s status as an “energy superpower”, at the expense of environmental protection and addressing climate change, while often seen to have an adversarial relationship with First Nations. In other words, the process was viewed by many stakeholders and members of the public to lack the legitimacy of being fair and objective. Gaetan Caron, former chair of the National Energy Board, argues the process for some was seen to be politicized before it was completed.

“When federal politicians take a stand on projects being assessed by a federal regulatory body like the NEB, they’re saying they’ve made up their mind before the regulatory review process has been completed, or in some cases, before it is even started,” argues Caron.9

The belief the process itself was flawed led to views becoming further alienated, leaving no means for opposing opinions to be challenged, discussed and measured. Interests remained in their silos and were not forced to deal with the tradeoffs needed to build consensus. The Liberal government’s energy and environment policy strategy needs to address directly and repair the public legitimacy issue. Sound public policy is in no small measure the art of persuasion. Legitimacy is not derived from a single policy. It comes in many forms, from political engagement with all sides of the debate, the public perception of determination by policymakers to accommodate interests in a fair and reasonable manner, and an independent, fact-based regulatory review process that supports those ends.

Efforts by the federal government which focus on a review of environmental processes are obviously a work in progress. The government has clearly established its priorities with two key elements of the strategy – First Nations and Indigenous people, and addressing climate change. Committing to an, as yet, undefined “nation-to-nation relationship” with Indigenous people has bought the government a measure of goodwill among First Nations, which see the government as serious about new terms of engagement. On climate change, the government has set clear targets and is engaging with the provinces in an effort to create the policies required to meet the national goals. Those are necessary steps.

What’s less clear is the government’s approach to energy development, specifically as it relates to the oil and gas sector and how it ranks in a priority with the others. The economic, fiscal and political fallout from the rapid decline in the oil sector has taken a heavy toll on Alberta and Newfoundland, and to a lesser extent Saskatchewan. It can be measured in the thousands of unemployed and the budgetary crunch that has hit the three provinces. But given the importance of the sector to the national economy, it has had ripple effects across the nation. Moreover, in a world where oil demand is going to continue to grow for decades and Canada has the second-largest reserves and is the third-largest oil producer in the world, oil production in this country is certain to increase, albeit at a slower pace than what had been forecast even three years ago.

This leads to the pivotal policy question. How does a new approach to energy and environment deal with often seemingly irreconcilable interests? It starts by acknowledging reality, beginning from the premise that the government will act in what it determines to be the national interest. How it gets to that determination must be based on a process that is seen as open, transparent, founded on sound evidence and seeking to balance interests. It will not lead to perfect outcomes for everyone, or even anyone, but it must be both rigorous and sensitive to the needs of a diverse nation, including First Nations.

Conclusion

The critical piece will be to restore the credibility of the National Energy Board as a fair, impartial and expert arbiter in weighing the merits of proposed developments against the environmental consequences. For decades, the NEB was regarded as among the best regulators in the world. Rightly or wrongly that reputation has been weakened. The cornerstone of a national energy and environment strategy must be to restore faith in the independence of the NEB. An EKOS public opinion survey of 2,100 Canadians done in February of this year found that slightly more than 50 per cent of Canadians expressed little or no confidence in the NEB.10 It reflects a fundamental division that must be bridged to reach a credible national energy and environment strategy.

An important step would be to reverse the 2012 decision that ended the practice of joint-review panels on major projects by the NEB and the Canadian Environment Assessment Agency. By expanding its mandate and capacity to again become effectively an expert national energy and environment forum would be a significant move in that direction. Coupled with it must be a parallel, independent and rigorous First Nations engagement process to ensure Indigenous Canadians’ voices are heard, considered and, where possible, accommodated as part of defining national interest.

Finally, framing it must be a clear and explicit overarching principle that states the national interest is paramount and determined by no single voice or interest, but the accommodation of many. That is not to say there won’t be entrenched interests that will never accept certain outcomes or that, in the end, political calculations won’t trump national interest. There is no painless or cost-free way forward. But as imperfect as it might be, it is still how sound policy is constructed for the benefit of the larger Canadian community. Expose Canadians to an open, rigorous and transparent process, as divisive as it might seem at times, and the majority will accept - perhaps grudgingly - an outcome that is less than they had wanted, but fair in what is an imperfect world.

Notes

- Government Launch Review of Environmental and Regulatory Processes to Restore Public Trust, June 20, Canadian Environment Assessment Agency

- World Bank Energy Use Tables

- p. 14, Canada’s Energy Future 2016, NEB

- NRCan 2015-16 Energy Facts Book

- p. 5, Canada’s Energy Future 2016, NEB

- p. 64, Energy Fact Book 2015-16, NRCan

- Speech to the AFN, July 12, 2016, Niagara Falls

- Ibid

- Straight Talk, Macdonald Laurier Institute, 2016

- Canadian Attitudes Toward Energy and Pipelines, EKOS Research, March 17, 2016

Dale Eisler

Dale Eisler has an extensive background in the federal public service and Canadian journalism. After a 25-year career in journalism with Saskatchewan and national publications, Dale spent 15 years in various senior roles with the Government of Canada, most recently as Assistant Deputy Minister for the Energy Security Task Force at Natural Resources Canada. Prior to that he spent four years serving as Canada’s Consul General in Denver, CO . Before his posting in the U.S., Dale was Assistant Secretary to the federal cabinet for Communications in the Privy Council Office and began his role in Ottawa as Assistant Deputy Minister for Communications in the Finance Department. He received the 2013 Joan Atkinson Federal Public Service Award of Excellence. He is the author of three book, including “False Expectations, Politics and the Pursuit of the Saskatchewan Myth” and, most recently in 2010, the historical fiction novel “Anton, a young boy, his friend and the Russian Revolution.”

People who are passionate about public policy know that the Province of Saskatchewan has pioneered some of Canada’s major policy innovations. The two distinguished public servants after whom the school is named, Albert W. Johnson and Thomas K. Shoyama, used their practical and theoretical knowledge to challenge existing policies and practices, as well as to explore new policies and organizational forms. Earning the label, “the Greatest Generation,” they and their colleagues became part of a group of modernizers who saw government as a positive catalyst of change in post-war Canada. They created a legacy of achievement in public administration and professionalism in public service that remains a continuing inspiration for public servants in Saskatchewan and across the country. The Johnson-Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy is proud to carry on the tradition by educating students interested in and devoted to advancing public value.

View Publication