A Difference-Maker: Changing how we think about accessibility and inclusion

Jennifer Gabrysh, MPA’13, grew up in Melfort, Saskatchewan an outdoorsy, sports-loving teen. She went on to play varsity soccer at the University of Lethbridge and to teach yoga and pilates while earning a bachelor’s degree at Lakehead University in Ontario. She spent summers studying French immersion in Quebec, tree planting in northern British Columbia and managing a fly-in fishing lodge in northern Manitoba.

By Bev Fast, Saskatoon-based freelance writerBecoming a Difference-Maker

Jennifer was the embodiment of active, and then a spinal cord injury in 2007 left her paralyzed from the shoulders down and everything changed. Well, that’s not quite right. The way she physically interacts with the world changed dramatically, but the qualities that shape her place in it did not.

Jennifer was the embodiment of active, and then a spinal cord injury in 2007 left her paralyzed from the shoulders down and everything changed. Well, that’s not quite right. The way she physically interacts with the world changed dramatically, but the qualities that shape her place in it did not.

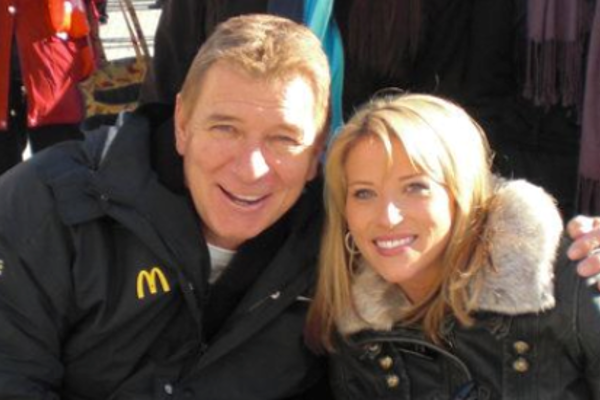

The Regina resident is an upbeat, outgoing personality. She is also passionately independent, a natural team leader and a skilled facilitator. Within months of her injury, she was volunteering as a youth leader and public speaker. She enjoyed helping others and was inspired by Rick Hansen’s legacy, so she became an ambassador for the Rick Hansen Foundation (RHF) in 2008. She organized several fundraising and awareness events and chaired the organizing committee for the Saskatchewan leg of Hansen’s 25th Anniversary Relay.

Two years post-injury, Jennifer enrolled in the Master of Public Administration program at Johnson Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy.

Rethinking the Future

“I started to think about the kind of career I could have while I was still in rehab. What was accessible? Where could I be useful?” Jennifer says. It was her own experience accessing government services that sparked her interest in public policy.

“I was using all kinds of health and social services, so I became knowledgeable about what the different levels of government provide. For example, I was told that I would have to live in long-term care for the rest of my life. I thought, ‘not an option,’ so I challenged it. I learned what was available to help me live independently. I applied for funding, learned to manage my own caregivers and moved into my own apartment.”

Soon after, Jennifer served on the Mayor’s Task Force on Access and with the Canadian Paraplegic Association. She also began volunteering for political campaigns, working for both Christine Tell, MLA for Regina Wascana Plains, and Kevin Doherty, MLA for Regina East. “Not only did I gain knowledge of government and the public policies that surround us,” she says, “but I thought, this is also an area where I have some insight.”

Online research led Jennifer to Johnson Shoyama. “I liked the fact that you learn what goes on behind the scenes in program development and policy decisions. So when I talked to some friends about the program and heard good things, I applied. I was thrilled when I got accepted.”

Jennifer’s studies had a local focus, and only partly of necessity. “Local issues are where I thought I could have to greatest impact,” she says. “When I worked as a constituency assistant for Minister Tell, I did a lot of things: schedule meetings, organize events, write speaking notes and engage people through social media. Most importantly, though, I spent a lot of time talking one-on-one when constituents called with their concerns. I really got to hear what mattered to people—flooding, housing, health care, the east bypass. At Johnson Shoyama, I focused on these areas as research projects. Not only were they relevant to my community, but I was able to consult and collaborate with different levels of government and local agencies. It was a great experience.”

As part of her program, Jennifer spent eight months as an intern alongside Scott Brown, executive director of the Policy Branch at the Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture, where she was involved in analyzing and evaluating issues that required policy options and recommendations. She followed that with a six-month consulting contract with SaskPower, where she presented a metrics project that involved researching and evaluating different resource pathways for a future electrical system.

Learning Together

Jennifer’s journey at Johnson Shoyama was a learning experience in more ways than one. The whole area of government administration was new to her (her BA was in history and French). “One of my favourite courses was the first one I took: public finance. It was eye-opening to learn what goes on behind the scenes—not just the numbers, but how governments prioritize and make decisions on what initiatives and programs to fund and how much to fund. You learn there’s a method to the madness, that governments and policy-makers do things for a reason.”

Her injury was a big part of the challenge. Jennifer had limited use of her hands, so she couldn’t take notes, write out formulas or sketch graphs. “My instructors had never had a student who couldn’t use their hands, so they had no idea how I would do it, and I didn’t either. We had to figure it out.”

Throughout her time at Johnson Shoyama, Jennifer had someone with her in class to take notes and help her get around. She used a specialized computer program. She hired a tutor to help with classwork and assignments. If there was something she couldn’t do on computer, she would go early to class to meet with her instructor to verbally explain her work.

Exams were the biggest challenge. “I couldn’t write them with everyone else. Instead, I met with my instructors. They would ask a question, I would have to think, formulate the answer in my head and then explain it. If it involved a graph, I would have to describe how to draw it. It was a lot of pressure. You don’t have the luxury of sketching your thoughts, you feel like you have to say the correct answer right off,” she says.

“I guess the benefit is that I worked hard to learn the material and then again to communicate it, so I really learned the concepts. I got good marks in all my classes.”

That viewpoint is a fundamental part of Jennifer. “I make it a point to have a smile on my face and a positive attitude—that’s a decision I made right after my injury,” she says. “I received a lot of encouragement from my family and friends. Their support helped me move out on my own, pursue my education and get involved in different activities.”

Jennifer’s upbeat attitude isn’t feigned. She doesn’t sugar coat the challenges and will tell you that living with a disability is hard. But she’s also using her public speaking and her volunteer work to quietly challenge society’s concept of inclusion. What does inclusion really look like—in the workplace, at school, in restaurants and shopping malls, at community events?

Becoming a Difference Maker

In the eight years since her accident, Jennifer has created a meaningful role for herself as a difference-maker. A difference maker, according to the Rick Hansen Foundation, is “an ordinary person who makes a positive difference in the lives of others. A difference maker can accomplish extraordinary things simply by thinking and acting beyond their own interests.”

In 2012, the Foundation named Jennifer one of Canada’s Top Difference Makers. Her journey through Johnson Shoyama was difference-making for the program—in 2013, she became the first person with a disability to graduate from the MPA program. That’s what a difference-maker does—they change how we think about accessibility and inclusion.

Jennifer has spent the last year doing motivational speaking and educating people about accessibility and difference making. She speaks about the key difference makers in her life and how they have encouraged her to make a difference in the lives of others.

“Inclusion is not only important for people with physical disabilities,” Jennifer says. “I want to lead policy change to support inclusion. I want to bring more awareness and provide insight into our social discourse to change the attitudes and barriers that affect so many of us. We should all be welcomed in an environment that encourages individuals to work to the best of their ability.”